OPINION

Nigeria’s counter-terrorism campaign and the role of its citizens in diaspora

By David Onmeje

Email address: daonmeje@outlook.com

Abstract:

This paper is an attempt to explore the various roles that Nigerians based abroad can play in the counter-terrorism campaign as the country grapples with the Boko Haram insurgency. The paper examines how the intellectual, professional and financial resources of the greater number of Nigerians in diaspora can be harnessed to give impetus to the fight against terrorism. The paper concludes that the Nigerian Diaspora have a vital role to play in the counter-terrorism effort of the country and that given the platform, coordination and motivation can have a significant impact on the country’s effort to overcome terrorism.

INTRODUCTION

In 2019, the conflict in North-eastern Nigeria entered its eleventh year. Since 2009, the Boko Haram insurgency has resulted in the death of tens of thousands of civilians and displaced millions across the Lake Chad region, which straddles Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria. Although major military campaigns in 2015–2016 succeeded in degrading the group’s territorial control, Boko Haram has proven remarkably adaptable in its guerrilla tactics.

Since the early years of the crisis, Nigeria’s international partners have cautioned that Boko Haram is unlikely to be defeated on the battlefield alone. They have stressed the need for a multidimensional response/approach that tackles the drivers of insecurity in the region, including chronic weaknesses in service delivery, corrupt governance and environmental degradation. However, the perception of limited leverage over Nigerian counterparts, restricted access to the country’s Northeast, and a response to the crisis shaped by the U.S.-led Global War on Terror limited donors’ focus on these governance dimensions on the ground.

In practice, international assistance came late, and donors struggled to identify viable national counterparts for stabilization programs. As a result, their efforts centred on supporting regional military efforts and responding to the large-scale humanitarian crisis.

Since early 2017, military gains and improved security in parts of north-eastern Nigeria have spurred a greater focus on conflict stabilization measures. At the international level, key donors set up the Oslo Consultative Group on the Prevention and Stabilization in the Lake Chad Region to coordinate their response activities. The Lake Chad Basin Commission and the African Union Commission have adopted a regional stabilization strategy, which highlights short-to-medium and long-term stabilization, resilience, and recovery needs.

In parallel, donors have also begun expanding bottom-up stabilization programs aimed at addressing the drivers of insecurity at the local level. These efforts have generally fallen into three main categories: programs aimed at strengthening local conflict prevention and mitigation systems, programs aimed at restoring local governance and essential services, and programs aimed at fostering social cohesion and ensuring the reintegration of former combatants.

However, one area that has not been given much attention is bringing the considerable personnel and skills of Nigerians in the Diaspora in the current counter-terrorism measures in Nigeria. This paper will explore the possible role this important stakeholder can play in Nigeria’s counter-terrorism efforts.

HISTORY OF TERRORISM IN NIGERIA

Boko Haram is a militant organization based in North-eastern Nigeria and also active in Chad, Niger and northern Cameroon. The group was founded in 2002 by Mohammed Yusuf upon the principles of the Khawaarij advocating Sharia law.

It turned into a violent extremist group in 2009 and has been responsible for the loss of lives in many parts of Northern Nigeria. Boko Haram previously existed as Jamā’at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da’wah wa’l-Jihād. One of the goals of the Boko Haram group is to champion for the establishment of an Islamic State, ruled by strict sharia law primarily in the Northern part of Nigeria where the majority of the populations are Muslims.

Boko Haram believes that democracy is too lenient and violates Islam. It also opposes the Westernization of Nigerian society and also the concentration of the wealth of the country among members of small political elite, mainly in the Christian south of the country. The roots of Boko Haram lie in the Islamic history of northern Nigeria, in which for some 800 years powerful sultanates centred on the Hausa cities close to Kano and the sultanate of Borno (roughly the region of the states of Borno and Yobe together with parts of Chad) constituted high Muslim civilizations.

These sultanates were challenged by the jihad of Shehu Usuman Dan Fodio (that lasted from 1802 to 1812), who created a unified caliphate stretching across northern Nigeria into the neighbouring countries. Dan Fodio’s legacy of jihad is one that is seen as normative by most northern Nigerian Muslims.

The caliphate still ruled by his descendants (together with numerous smaller sultanates), however, was conquered by the British in 1905, and in 1960 Muslim northern Nigeria was federated with mostly Christian southern Nigeria. The Muslim response to the Christian political ascendency was the move during the period of 2000-2003 to impose Sharia in 12 of the northern states in which they predominated. For the most part, the imposition of Sharia brought the previously feuding Muslim groups together, and there was no further use of takfiri (accusations of being non-Muslim).

While the imposition of Sharia did satisfy the official manifestations of Islam in the north (both Sufi and Salafi), it is clear that radicals who were takfiris doctrinally such as members of Boko Haram were left outside. There is no doubt that the suppression operation of 2009, and the killing of Muhammad Yusuf by Nigerian security forces in July of that year, was a turning point for Boko Haram.

The group was frequently said at this time to be defunct. In September 2010 (coinciding with Ramadan), however, Boko Haram carried out a prison break (said to have released some 700 prisoners). After that, the group began operations again. The targeted assassinations are the most revealing, involving political figures, such as Abba Anas bin `Umar (killed in May 2011), the brother of the Shehu of Borno, and secular opposition figures (Modu Fannami Godio, killed in January 2011), but also prominent clerics such as Bashir Kasahara, a well-known Wahhabi figure (killed in October 2010), Ibrahim Ahmad Abdullahi, a non-violent preacher (killed in March 2011), and Ibrahim Birkuti, a well-known famous preacher who challenged Boko Haram (killed in June 2011).

The shootings of these prominent clerics seem to be in accord with Boko Haram’s purification agenda concerning Islam. Boko Haram related violence has mostly been confined to Nigeria’s Northeast, in Adamawa, Borno and Yobe states. It has been most heavily concentrated in Borno, with the brunt of the violence borne by Maiduguri, Gwoza, and Kukawa.

Violence has also become common south and east of Maiduguri, along the border with Cameroon’s Far North Region, and around Lake Chad. There have been sporadic incidents in places such as Nigeria’s Middle Belt and the capital of Abuja that have been attributed to Boko Haram.

Boko Haram has adopted suicide attacks as an essential tactic in its struggle against government authority. Over the past seven years, Boko Haram has demonstrated flexibility. It remains a formidable threat to the Nigerian state despite losing much of its territory. Though the group is undoubtedly less potent than it was in 2015, there is no sign that the government will defeat it in the foreseeable future without bringing on-board inputs from various quarters such as the Nigerians in the Diaspora.

UNDERSTANDING TERRORISM

Understanding Insurgency and Terrorism have become one of the most security challenges for many countries in the world. Due to the threat terrorism poses to international peace and security, it has attracted much attention globally. Although there are international instruments which condemn terrorism and call for its suppression and elimination, there remains the primary challenge of a lack of a universally accepted legal definition for terrorism. The lack of specificity in definition has continued to pose the risk of non-standardized, insufficient or incorrect application and implementation of counter-terrorism measures.

There is a long-standing consensus in the academic community over the disagreement surrounding the conceptual and operational definition of terrorism. Both the theoretical conceptualization and the empirical manifestation of terrorism are highly contested based on state, national, political, geopolitical, religious and even ideological constellations, giving rise to not one but many manifestations of terrorism, differing from one region to another, one sub-region to another and one country to another.

However, even though there is still a lack of agreement on what terrorism is, attempts at arriving at a definition have been made. At the 1999 Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism, the Organization of African Unity (OAU) defined an act of terrorism as “any act which is a violation of the criminal laws of a State Party and which may endanger the life, physical integrity or freedom of, or cause serious injury or death to, any person, any number or group of persons or causes or may cause damage to public or private property, natural resources, environmental or cultural heritage”.

Similarly, the 2015 Global Terrorism Index (GTI) report defines terrorism as “the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by non-state actors to attain a political, economic, religious or social goal through fear, coercion or intimidation”.

Also, Forest and Giroux, defined terrorism as a tactic that uses violence or threat of violence as a coercive strategy to cause fear and political intimidation. Insurgency, on the other hand, is a strategy adopted by groups which cannot attain their political objectives through conventional means or by a quick seizure of power.

Insurgency could also be defined as any kind of armed uprising against an incumbent government.

It is characterized by protracted, asymmetric violence, ambiguity, the use of complex terrain (jungles, mountains, and urban areas), psychological warfare, and political mobilization which are all designed to protect the insurgents and eventually alter the balance of power in their favour. In his book titled ‘Globalization and Insurgency’,

Mackinlay defined insurgency as the actions of a minority group within a state who are intent on forcing political change utilizing a mixture of subversion, propaganda and military pressure, aiming to persuade or intimidate the broad mass of people to achieve their aim. Insurgency could start as a social protest, from a given group of people, who feel continuously marginalized in the affairs of government. From the preceding, terrorism and insurgency generally arise from similar causal conditions, terrorism often being employed as a tactic within a broad framework of an insurgent campaign. For example, groups like Al-Shabaab in Somalia and Boko Haram in Nigeria are known to employ a mix of insurgent and terrorist tactics. It is also clear that terrorism can stand alone, as in the case of known terrorist groups such as Al-Qaeda and Islamic States (IS).

CHALLENGES OF COUNTER-INSURGENCY/COUNTER-TERRORISM IN THE SAHEL

Faced with the complex and sophisticated terrorist attacks, stakeholders in the Sahel region have responded by deploying troops aimed at combating terrorism. Given the level of terrorist activities, it comes as no surprise that the region as a whole has undergone a process of securitization in recent years, which has resulted in a multitude of forces on the ground.

The current deployment in the Sahel includes G5 Sahel Joint Force, Operation Barkhane, Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF) and United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) and well as the national armies of the respective countries. The trends in terrorist activities and counter-terrorism efforts observed in the Sahel is somewhat not encouraging. Counter-terrorism response has been fraught with a lot of difficulties and challenges leading to the worsening and deterioration of the security situation in most countries of the Sahel.

This has the potential of spreading to other neighbouring countries. Some shortcomings could be cited. Undermining the success of the counter-terrorism efforts, is the discontent among troops, as exemplified by instances of military personnel refusing to take part in operations or abandoning their posts.

This is further compounded by the mistrust among troop-contributing countries with some troops always in a hurry to announce victory without crediting the entire force. This has often led to disagreements among countries contributing troops to the counter-terrorism efforts, thereby derailing the progress of the force.

Counter-terrorism operations require specific training, equipment, intelligence, logistics, capabilities and specialized military preparation. It would seem unrealistic to expect any significant improvement on this front in the short and medium terms, partly because of funding constraints and delays in deployment for some of the missions, such as G5 Sahel Joint Force.

Lack of financial capability of troop-contributing countries to adequately resource personnel has resulted in logistical constraints of deployed troops. Corruption within government and state security apparatus has also contributed to the logistical constraints of the troops as there have been cases of politicians and senior military personnel misapplying funds meant of equipment and retooling of troops.

Lack of coordination, cooperation, and collaboration among the many deployed troops in the Sahel is a significant setback confronting the fight against terrorism. There have been cases of some deployments refusing to share intelligence with other contingents operating in the same theatre, thereby undermining their military capability to curtail the scourge of terrorism. The delay in the response of some non-national contingents to distress calls from national authorities of the member states in which they are deployed is also another challenge.

Besides, it has become apparent that the ever-growing focus on counter-terrorism, underscored by significant international (Western) efforts, seeks to abandon the implementation of peace accords and agreements such as the 2015 Algiers Peace Accord in Mali, which is crucial not only for a security solution but also for a political resolution of the conflict.

In some cases also, the security situation has made it difficult for governments to implement reforms needed to address root causes fuelling the spread of terrorism. Similarly, the influx of foreign support and resources to address security challenges such as terrorism and human trafficking appears to fail to address much-needed reforms in state behaviour, governance and justice, which are significant factors in driving violence and radicalization.

AN ALL-INCLUSIVE APPROACH TO COUNTERING TERRORISM

In order to organize themselves, and to plan and carry out attacks, terrorists need recruits and supporters, funds, weapons, the ability to travel unimpeded, other forms of material support (e.g., means of communicating, places to hide), and access to vulnerable targets. Therefore, effectively countering acts of terrorism requires a comprehensive and strategic approach, relying on a broad range of policies and measures.

An all-inclusive approach to counter-terrorism often encompasses several objectives, addressing different chronological stages in the occurrence of terrorism. These objectives can be broadly categorized as:

• Preventing men and women from becoming terrorists;

• Providing opportunities and support to individuals on a path to, or involved in, VERLT to disengage;

• Denying terrorism suspects the support, resources and means to organize themselves or to plan and carry out attacks;

• Preparing for, and protecting against, terrorist attacks, in order to decrease the vulnerability of potential targets, in particular, critical infrastructure;

• Pursuing terrorist suspects to apprehend them and bring them to justice; and

• Responding to terrorist attacks through proportionate measures to mitigate the impact of such attacks and to assist victims.

Countries have an obligation to protect against acts of terrorism, and this requires that they put particular emphasis on preventing terrorism. This is reflected in their international legal obligations and political commitments.

The UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy notably defines a holistic approach to counter-terrorism that includes:

• Measures to address conditions that are conducive to the spread of terrorism;

• Measures to prevent and combat terrorism; and

• Measures to ensure respect for human rights for all and the rule of law as the fundamental basis of the fight against terrorism.

UN Security Council resolution 1373 (2001) imposes a legally binding obligation on all states to establish appropriate legislative, regulatory and institutional frameworks, including, to:

• Refrain from providing any form of support, active or passive, to entities or individuals involved in terrorist acts;

• Prevent and suppress the financing of terrorism;

• Suppress the recruitment of members of terrorist groups;

• Eliminate the supply of weapons to terrorists;

• Prevent the movement of terrorists or terrorist groups;

• Deny safe havens to those who finance, plan, support or commit terrorist acts, or provide safe havens;

• Ensure that any person who participates in the financing, planning, preparation or perpetration of terrorist acts or in supporting terrorist acts is brought to justice; and

• Afford each other the most significant measure of mutual legal assistance in connection with criminal matters related to terrorism.

UN Security Council resolution 1456 (2003) and subsequent resolutions oblige states to ensure that any measure taken to combat terrorism complies with international law, in particular international human rights law, refugee law and humanitarian law.

DIASPORA AND COUNTER-TERRORISM STRATEGY

Counter-terrorism requires a multi-faceted approach that is all-inclusive and addresses not only the manifestation of terror-related activities but also its underlining causes while also carrying everybody along. The Nigerian Diaspora community can be beneficial in every stage and facet of the strategy to counter insurgency and bring about the much-needed peace to the Northeast of the country.

One of the most effective counter-terrorism measures which can address the problem from its root cause is education. Education does not only help this potential terrorist a chance to get out of poverty but also help in reshaping perception. Nigerian Diasporans can help to mobilize and provide both human resources and educational material needed to help educate the children in this region that are prone to the insurgency.

Counter-terrorism has a significant international dimension and it’s impossible for a country to go it all alone. Significant pressure and lobby is needed to draw support of countries with the expertise and resources to help as well as other international partners. The Nigerian Diaspora community can play a role in lobbying and pressuring international organizations and the big countries to provide much-needed assistance.

Rehabilitation of victims of terror activities is an essential area in counter-terrorism. This required a lot of human resources and resources as the insurgency has displaced more than a million people. The Diaspora community can get actively involved in the rehabilitation effort using their connection to mobilize resources from charity organization all over the world and providing their expertise in rehabilitation and counselling.

The Nigerian diaspora community are significant players all over the world in the area of information and communication technology. They can help the counter-terrorism campaign in the area of gathering information and analyzing them. Getting the right information will help in proffering the correct solution to the problem of terrorism.

Technology can help give significant efficiency and effectiveness to both military and civilian operations in the counter-terrorism campaign. The Nigerian diaspora community can involve Nigerian inventors all over the world to help in providing proprietary technologies and other technological solution that will give precision to both military and political solution to the insurgency in Nigeria.

The counter-terrorism campaign can also draw many volunteers from Nigerians in the diaspora. Volunteers with diverse skill sets and professional background can be drawn from all over the world, which will have a significant effect on the fight against terrorism.

CONCLUSION

There is no doubt that the counter-terrorism campaign has not been effective enough to have a significant impact. There is a great room for improvement in every front, either in terms of finance, people, technology, ideas, and collaboration. The Diaspora community can help to bridge the gaps in this area significantly. The Diaspora community should be given the platform to bring in their significant resources, professional experience, inventions and exclusive contacts to help in giving the much-needed impetus to the counter-terrorism campaign. Nigeria has professionals in different field of endeavour all over the world; it will be astute to draw on the knowledge to bring terrorism to an end.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Diaspora community should explore the possibility of bringing inventors, especially those in the military industry to help in the modernization of the Nigerian army. Israel leans significantly on its diaspora population in strengthening its security forces against insurgency in that country.

The Diaspora community should become a vanguard for countering fake news against the country’s military with facts that are available on government website.

The Diaspora community should maximize the significant population of Nigerians all over the world to draw attention and support to the fight against terrorism. The state of Israel actively engaged their citizens abroad to lobby for both financial and political support for its fight against insurgency and terrorism.

The Diaspora community in international media circles just like nationals of other countries do should use their mediums to promote efforts by the Federal Government and its military.

The Diaspora community should begin the process of mobilizing volunteers from abroad for much needed humanitarian effort as part of the counter-terrorism effort.

Indian has used the ICT knowledge of it Diaspora in the gathering of information in gathering information in its fight against insurgency. Nigeria can do the same by taping on Nigerians ICT experts abroad.

The Diaspora community using its proximity to the International Criminal Court should form pressure groups that will ensure that sponsors and promoters of terrorist groups in Nigeria are arrested and prosecuted.

REFERENCES

1. Adepoju, A., 2003, ‘Continuity and Changing Configurations of Migration to and from the RepublicofSouthAfrica.

2. Kenneth Omeje 2007, The Diaspora and Domestic Insurgencies in Africa.

3. Bonn International Center for Conversion Diasporas and Peace, A Comparative Assessment of Somali and Ethiopian Communities in Europe, (2010).

4. Maxim Worcester: Combating Terrorism in Africa.

5. Akanji, O. O., 2019. Sub-regional Security Challenge: ECOWAS and the War on Terrorism in West Africa.

6. Banunle, A. & Apau, R., 2018. Analysis of Boko Haram Terrorism as an Emerging Security Threat in Western Sahel; Nigeria in Focus.

7. Organization of African Unity (1999). 1999 OAU Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism.

8. Forest, J.J. & Giroux, J., 2011. Terrorism and political violence in Africa: Contemporary trends in a shifting terrain.

OPINION

Enhancing Workplace Safety And Social Protection: The Role Of The Employees’ Compensation Act, 2010

Presentation by

Barr. Oluwaseun M. Faleye

Managing Director/Chief Executive, Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund

At the 65th Annual General Conference of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA)

International Conference Centre, Enugu

24th August 2025

Introduction

Distinguished colleagues, esteemed members of the Bench and Bar, fellow policymakers, captains of industry, and ladies and gentlemen.

It is both an honour and a privilege to stand before this distinguished assembly at the 65th Annual General Conference of the Nigerian Bar Association. The NBA has, over decades, remained the conscience of our nation, a defender of rights, a champion of justice, and a custodian of the democratic ideals that gives meaning to our collective existence.

The theme of this year’s conference, “Stand Out, Stand Tall!” is more than a slogan. It is a call to courage, to excellence, and to visionary leadership. It challenges us, as thought-leaders and nation-builders, to lift our society beyond mediocrity and to confront the existential issues that hinder Nigeria’s march toward greatness.

I stand today to speak directly to one of those existential issues, the safety of our workplaces and the social protection of our workers. These are not peripheral concerns; they touch the very core of our humanity, our economy, and our pursuit of sustainable national development.

In focusing on “Enhancing Workplace Safety and Social Protection: The Role of the Employees’ Compensation Act, 2010,” I aim to situate our conversation at the intersection of law, labour, and human dignity.

Work is not merely an economic activity; it is central to human identity and social progress. Through work, families are sustained, communities are developed, and nations are built. The dignity of labour, so deeply rooted in our cultural and constitutional ethos, affirms that every worker deserves protection, not just in the fruit of their labour, but also in the very process of labouring.

Yet, the paradox remains: while work empowers, it can also endanger. The same factories that generate wealth can expose workers to industrial hazards; the same oil rigs that earn foreign exchange can subject workers to occupational illnesses; the same construction sites that build our cities can also claim lives in accidents.

This paradox highlights the urgency of workplace safety and the necessity of social protection. It is not enough for a nation to pursue economic growth; such growth must be inclusive, humane, and protective of those whose sweat oils the engines of development.

The Global Context: Grim Realities of Workplace Hazards

Permit me to share with you the grim realities of workplace hazards, and these statistics are not mine; they were provided by the International Labour Organization:

Each year, over 2.8 million workers die from occupational accidents and work-related diseases.

Over 374 million workers suffer non-fatal injuries annually, many of which lead to long-term disabilities or reduced quality of life.

The economic cost of poor occupational safety and health is estimated at nearly 4% of global GDP annually, a staggering burden on productivity, healthcare systems, and social welfare.

These statistics are not just numbers; they are human lives, families disrupted, and dreams shattered. They remind us that workplace safety is not a privilege to be enjoyed by a few but a right owed to all.

Within the context of our own country, our peculiar socio-economic realities make workplace safety and social protection even more urgent.

Data Gaps: Accurate national data on workplace accidents remains limited. However, the Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund, through its Employees’ Compensation Scheme, continues to receive increasing claims from affected workers and employers.

High-Risk Sectors: Industries such as construction, oil and gas, and manufacturing remain prone to frequent and sometimes fatal workplace accidents. Poor adherence to safety standards, inadequate enforcement, and limited awareness exacerbate the problem.

Informal economy Vulnerability: With over 80% of Nigeria’s workforce engaged in the informal economy, millions of workers remain outside structured occupational safety nets, leaving them and their families highly vulnerable in the event of accidents or diseases.

Cultural and Institutional Weaknesses: In many workplaces, safety culture is weak. Employers often see safety compliance as a cost rather than an investment, while workers themselves may lack training or incentives to prioritize safety.

The outcome of these realities is clear: rising workplace accidents, preventable occupational illnesses, and increasing claims for compensation. More importantly, the loss of human capital undermines national productivity and deepens poverty traps for affected families.

Why Workplace Safety and Social Protection Matter

Workplace safety and social protection are not optional luxuries; they are fundamental pillars of social justice, human dignity, and economic sustainability.

They ensure dignity, peace of mind, and assurance that one’s labour will not become a source of tragedy for one’s family.

They enhance productivity, reduce downtime due to accidents, and foster industrial harmony.

They reduce the burden on healthcare systems, mitigate poverty, and enhance national competitiveness.

In essence, workplace safety and social protection are as much about human rights as they are about economic development. A nation that fails to protect its workers fails to protect its future.

The Employees’ Compensation Act, 2010: A Paradigm Shift

The enactment of the Employees’ Compensation Act (ECA), 2010 marked a watershed moment in Nigeria’s labour and social security landscape. It replaced the Workmen’s Compensation Act, a law that had long been criticized for its narrow scope, rigidity, and employer-centric bias.

For decades, Nigerian workers and their families bore the brunt of a compensation system that failed to adequately recognize the evolving realities of modern workplaces. The law operated within the framework of an industrial era that no longer reflected the complex dynamics of contemporary employment relationships. Workers were often left destitute after workplace accidents, while employers faced prolonged litigation that neither restored the injured nor secured industrial harmony.

The ECA 2010 emerged as both a legal reform and a moral commitment, aligning Nigeria with international best practices, especially as recommended by the International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions on occupational safety, health, and social security.

1. Comprehensive Coverage

One of the most remarkable contributions of the ECA is its expansive scope.

It applies to all employers and employees across both the public and private sectors, creating a unified national standard.

It extends protection beyond physical accidents to include:

Occupational injuries sustained in the course of work.

Occupational diseases arising from exposure to harmful substances or hazardous environments.

Permanent and temporary disabilities, whether partial or total.

Mental health challenges linked to workplace stress, trauma, or hazards, an innovative inclusion that reflects global recognition of psychosocial risks.

By broadening its ambit, the ECA acknowledges the complex and evolving nature of work, ensuring that no worker is left behind simply because their injury or illness does not fit into a narrow definition.

2. Employer Contribution System

The ECA dismantled the inequitable structure of the past where individual employers bore sole liability for compensation. Under the Workmen’s Compensation Act, an employer had to directly compensate an injured worker, often leading to disputes, prolonged court cases, and financial strain.

In contrast, the ECA introduced a collective, pooled system where employers across sectors contribute to a central fund administered by the Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund. The Fund ensures that resources are available upfront to address claims promptly, rather than waiting for the outcome of litigation.

The pooled risk model reflects the principle of social solidarity, spreading risks and costs across the economy, rather than isolating them within a single workplace.

This mechanism not only secures workers’ rights but also protects employers from the unpredictability of individual liability. It shifts the focus from blame to shared responsibility.

3. Quick and Fair Compensation

The ECA was deliberately designed to speed up and humanize the compensation process.

Injured workers are entitled to immediate medical treatment without the burden of proving employer negligence. Beyond treatment, workers receive physical rehabilitation, vocational training, and support for reintegration into the workforce.

In cases of permanent or temporary disability, the law guarantees structured financial support. Dependents of workers who lose their lives in workplace accidents receive death benefits, ensuring families are not plunged into poverty.

This no-fault principle, where workers are compensated regardless of negligence, removes the adversarial tension of litigation. It prioritizes healing, dignity, and security over legal wrangling.

4. The Social Security Dimension

Perhaps the most transformative feature of the ECA is its broad social security orientation. Unlike its predecessor, the Act is not limited to post-accident compensation but also embraces prevention, rehabilitation, and reintegration.

5. A Balance between Rights and Responsibilities

The genius of the Employees’ Compensation Act lies in its balance.

For workers, it guarantees protection without the hurdles of litigation or the uncertainty of employer discretion. For employers, it eliminates the risk of crippling lawsuits and provides predictable contributions into a shared pool. For the nation, it strengthens social justice, reduces systemic poverty traps, and aligns Nigeria with international labour standards.

Thus, the ECA 2010 represents more than just legal reform, it is a paradigm shift towards a modern, inclusive, and humane labour ecosystem. It affirms that in Nigeria’s pursuit of growth, the lives and dignity of workers cannot be treated as expendable.

Current Realities and Challenges

Fifteen years after its enactment, the Employees’ Compensation Act 2010 has undoubtedly transformed Nigeria’s labour compensation framework. The establishment of a no-fault, pooled compensation system has brought hope to thousands of workers and their families. Yet, as with most legal and policy reforms, the journey from law on paper to lived reality has been uneven.

While progress has been recorded in claims processing, accident coverage, and legal clarity, several persistent and emerging challenges continue to undermine the Act’s full impact.

Low Employer Compliance

One of the most pressing realities is incomplete employer compliance, especially among Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs).

Despite being the backbone of Nigeria’s economy, accounting for over 80% of jobs and nearly 50% of GDP, many SMEs either fail to register with the NSITF or under-declare their workforce size and wage bills.

Reasons for non-compliance include limited awareness of legal obligations, perceived cost burden of contributions and weak enforcement and monitoring mechanisms.

The result is that millions of workers in SMEs remain outside the protective umbrella of the Act, leaving them vulnerable to poverty traps in cases of workplace accidents.

This compliance gap undermines the spirit of universality and inclusivity envisioned by the law.

Limited Awareness Among Workers and Employers

A large proportion of Nigerian employees remain unaware of their rights under the Act.

Many workers do not know they are entitled to compensation in cases of occupational injury or disease. In some cases, employers exploit this ignorance by discouraging claims or providing token settlements instead of due benefits.

Even among educated workers, there is often confusion between ECA entitlements and other social protection schemes like pensions or health insurance.

Awareness campaigns have been sporadic, with limited penetration outside major cities. For a country with over 70 million workers in the informal and formal sectors combined, sustained national enlightenment is essential and we are committed to doing that to ensure that Nigerian workers understand their rights and the benefits associated with complying with the Employee’s Compensation Act.

Under-Reporting of Workplace Accidents

Another major challenge is the systemic under-reporting of workplace accidents and occupational diseases.

Many employers fear that reporting incidents will attract sanctions, regulatory scrutiny, or reputational damage.

Workers themselves sometimes avoid reporting for fear of losing their jobs, stigmatization, or bureaucratic delays in accessing benefits. This results in a data gap, making it difficult for policymakers and regulators to accurately assess the scope of occupational risks in Nigeria.

For instance, while the International Labour Organization estimates that 2.8 million workers die globally every year from work-related causes, Nigeria’s official records capture only a fraction of actual cases. The absence of reliable, comprehensive data limits the country’s ability to design targeted interventions.

Changing Work Dynamics in a New Economy

The world of work is changing rapidly, and Nigeria is no exception. The ECA 2010, while progressive, must continuously adapt to these evolving realities.

Platforms like ride-hailing services, delivery apps, and freelance digital work create new categories of workers who often fall outside traditional employer-employee relationships.

As I have mentioned, over 80% of Nigerian workers operate in the informal economy, where workplace safety standards are often non-existent. Extending the ECA’s protections to this vast segment remains a daunting but necessary task.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated remote work adoption, raising new questions about what qualifies as a “workplace accident” when work is performed from home.

With automation, robotics, and artificial intelligence entering workplaces, new categories of hazards, such as ergonomic injuries, mental stress, or even cyber-related risks are emerging.

These shifts demand dynamic legal interpretation and possible amendments to ensure that the ECA remains relevant in a rapidly changing labour market.

These realities highlight the need for multi-sector collaboration, linking labour law enforcement with broader economic reforms, social welfare, and national development strategies.

The Role of Lawyers and Policymakers

The implementation and impact of the Employees’ Compensation Act, 2010 cannot rest on the NSITF alone. Like every piece of transformative legislation, the ECA lives and breathes through the interpretation, advocacy, and enforcement carried out by lawyers, judges, and policymakers.

Apart from our expectation of you as advocates of the efficacy and importance of the Employees’ Compensation Scheme, the most crucial expectation we have of you lawyers and leaders of the bar here is to lead by example.

We must comply with the law ourselves. We must ensure that all law firms practicing law in Nigeria subscribe to the Employees’ Compensation Scheme.

As you all know, law practice, particularly those of our colleagues engaged in dispute resolution practices comes with its risks. Lawyers travel to different parts of this country practicing their trade, advocating and defending clients. These journeys come with risk.

For the corporate and commercial lawyers, they tend to sit for hours reviewing documents, negotiating agreements and also do a lot of traveling in the course of work. These long hours at work stations often leads back and spinal injuries.

Indeed, the pressure of work could sometimes lead not only to physical challenges but to mental stress as well. Yet, majority of our law firms are not complying with the Employees’ Compensation Scheme to give their employees, fellow lawyers the safety net the law prescribed and which they all deserve.

The NBA must do more and ensure that all law firms comply with the Employees’ Compensation Act to safeguard our workforce. And it is my hope that the Welfare Committee of the NBA will champion this initative.

We must ensure that evidence of compliance with the ECA becomes part of documentation for aspiring to be Senior Advocates. As part of the law firm inspection exercise towards the conferment of silk, I urge us to ask for evidence that law firms are complying with the Employees’ Compensation Act akin to our position on payment of pension obligations for lawyers.

Corporate lawyers are often the first point of contact for businesses seeking to understand their obligations under labour laws. It is therefore incumbent on them to educate employers, particularly SMEs on the necessity of compliance with the ECA, not only as a legal requirement but as a strategic business investment.

When disputes arise, lawyers must uphold the spirit of social justice embedded in the Act, ensuring that compensation claims are pursued diligently and without undue delay.

Beyond individual cases, the legal community must serve as advocates of systemic reform, engaging with government and civil society to strengthen workplace safety and employee protections.

The Nigerian Bar Association can serve as a bridge between policymakers and the workforce, ensuring that the law keeps pace with global best practices and local realities.

As to the role of the judiciary, we acknowledge that the courts play a pivotal role in giving life to the Act. Therefore, judicial interpretation must consistently reflect the protective, worker-centred philosophy of the ECA.

Landmark rulings can set precedents that discourage employers from evading responsibilities and embolden employees to seek justice without fear.

The judiciary must guard against narrow, technical interpretations that undermine the law’s purpose. Instead, it must elevate the principle that the protection of human dignity is paramount.

From the legislative perspective, our law makers must recognize that the labour market is evolving faster than ever before. Regular amendments to the ECA 2010, whether to address the gig economy, informal economy realities, or technological hazards, are necessary to maintain its relevance.

The ECA 2010, therefore, should not be viewed solely as a labour statute, but as a human rights instrument, a guarantee that every Nigerian worker deserves protection, dignity, and a safety net against the uncertainties of life.

The Future of Workplace Safety and Social Protection in Nigeria

Looking forward, the NSITF’s vision is to build a comprehensive social security architecture for Nigeria, with the ECA as its cornerstone. The Act laid the foundation, but the building of a resilient, inclusive, and future-ready system requires bold innovations.

The Fund is embracing technology-driven solutions to improve speed, transparency, and accountability.

Real-time reporting systems will allow employers and workers to instantly report accidents through digital platforms, ensuring quicker responses. Data analytics will enable predictive modelling, identify high-risk sectors and help prevent accidents before they happen.

E-certificates of compliance which we have already introduced, are reducing fraud and making compliance verification seamless.

The ECS’s future lies in creating innovative schemes tailored to suit the informal economy. Pilot projects are already exploring contributory micro-schemes that will allow even low-income workers to enjoy compensation and protection.

Extending coverage to the informal economy is not only a matter of justice but also of national productivity, since these workers drive much of Nigeria’s growth.

Compensation after injury is important, but prevention is better, cheaper, and more sustainable. The Fund is investing in workplace safety audits to identify risks early, we are undertaking compliance inspections with deterrent sanctions for violators and enhancing our capacity through programs, training employers and employees on global best practices in occupational safety and health (OSH).

By fostering a culture of prevention, Nigeria can reduce workplace accidents and improve productivity across sectors.

Nigeria must continue to harmonize with international standards by ratifying and implementing relevant ILO conventions on occupational safety and health. We must learn from other countries with mature compensation frameworks and systems.

We must leverage partnerships with global organizations to build capacity, fund safety initiatives, and modernize systems. These sorts of global alignment ensures that Nigerian workers are not left behind in an increasingly interconnected labour market.

Conclusion

Distinguished colleagues, learned friends, ladies and gentlemen, the Employees’ Compensation Act, 2010 is more than a statute on the books. It is a covenant of dignity, a shield of protection, and a beacon of social justice for the Nigerian worker.

It represents a promise, that when a worker is injured, they will not be abandoned; when a family loses its breadwinner, they will not be thrown into despair; and when an employer invests in safety, they will be rewarded with loyalty, productivity, and peace.

To truly “Stand Out, Stand Tall,” as this conference theme challenges us, we must rise above rhetoric and build a society where no worker leaves home in fear that their daily bread could cost them their life, no child is forced out of school because an injured parent can no longer provide and no widow or widower is left destitute because justice was delayed or denied.

This is not just about labour law, it is about the soul of our nation. A society that protects its workers protects its future. A nation that neglects its workforce undermines its destiny.

The call before us today is clear.

Lawyers must be the vanguard of compliance and justice, using their knowledge to protect the vulnerable.

Policymakers must be visionaries, ensuring that our laws evolve with the realities of modern work.

Employers must see safety and social protection not as costs, but as investments in their people and their productivity.

And institutions like the NSITF must continue to lead with innovation, transparency, and courage.

If we do this, we will build more than safe workplaces, we will build a safer Nigeria. We will do more than compensate accidents, we will prevent them. We will not just write laws; we will write legacies.

Together, we can build a Nigeria where every citizen can stand out in excellence and stand tall in dignity.

Thank you.

May God bless our workers.

May God bless the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Oluwaseun Faleye

Managing Director/CE

Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund

OPINION

US Visa Applicants And Social Media Disclosure: A Risky Overreach With Dire Consequences For Nigerians

By Olufemi Soneye

The United States has recently implemented a sweeping immigration policy requiring nearly all visa applicants to disclose their social media handles and digital histories. Framed as a tool to bolster national security, counter terrorism, and curb cybercrime, the measure may appear reasonable on paper. But for Nigerians and many others from countries with vibrant, digitally active populations the consequences are troubling and far-reaching.

Nigeria’s dynamic online culture is marked by satire, political commentary, and spirited debate. In this context, posts that are humorous or culturally specific may be misunderstood by foreign officials unfamiliar with the nuances of local discourse. What may be a harmless meme or satirical remark in Nigeria could be wrongly interpreted as extremist, subversive, or fraudulent by US immigration authorities.

This does not merely pose a risk to individual visa applicants. It threatens broader societal values such as freedom of expression, cultural authenticity, and civic engagement. It also risks further straining US–Nigeria relations at a time when collaboration and mutual respect are more important than ever.

The US government maintains that social media activity provides valuable insight into a visa applicant’s character, affiliations, and potential risks. In an age where radicalization and misinformation can proliferate online, there is some logic to this argument. However, in practice, it opens the door to arbitrary interpretations, biased judgments, and significant invasions of privacy.

Disturbing cases have already emerged. A Norwegian tourist was recently denied entry into the United States after officials discovered a meme referencing US Vice President J.D. Vance on his phone. In another case, a Nigerian businesswoman with a valid visa was turned away at a US border after immigration officers reviewed her Instagram messages and claimed her online activity contradicted the nature of her visa. These examples illustrate how subjective and potentially discriminatory the enforcement of this policy can be.

Adding to the concern, the US has launched a pilot program requiring visa applicants from select countries to pay a $15,000 bond. The initiative, which began with Malawi and Zambia, reportedly targets nations with high visa overstay rates and could be expanded. It sends a chilling message: that citizens of certain countries are presumed guilty until proven otherwise.

For Nigerians, the implications are especially severe. Privacy is the first casualty. Applicants must now submit their digital footprints including personal conversations, private networks, and online affiliations to a foreign government. Freedom of expression is the next victim. Young Nigerians, who make up the majority of users on platforms like X (formerly Twitter), TikTok, and Instagram, may begin self-censoring out of fear that political opinions or cultural commentary could jeopardize their chances of traveling or studying abroad.

This policy disproportionately impacts the very demographic that is driving Nigeria’s innovation, creativity, and international reputation. Students, entrepreneurs, artists, and professionals, the most globally engaged Nigerians are now the most vulnerable to misinterpretation and arbitrary visa denials. What constitutes a “red flag” is alarmingly subjective: a meme, a retweet, or a political statement could be enough to trigger rejection, with little recourse for appeal.

There are broader implications for the Nigerian diaspora and global mobility. Social media has long served as a bridge connecting Nigerians abroad with their homeland, facilitating civic dialogue, cultural exchange, and philanthropic engagement. If digital expression becomes a liability, this bridge may weaken, silencing a vital global voice and undermining transnational ties.

Moreover, the policy risks reinforcing damaging stereotypes. Nigerians already contend with international biases linking the country to fraud or instability. A policy that scrutinizes their digital lives under a security lens could deepen mistrust, alienate young professionals, and diminish goodwill toward the United States.

The global repercussions are also concerning. If the US, a global standard-setter in immigration policy, normalizes the collection and evaluation of applicants’ private digital histories, other countries may follow suit. This would set a dangerous precedent, where opportunities for global mobility depend not on merit or intent, but on an algorithmic analysis of social media behavior often devoid of cultural context.

National security is undeniably important. But it must be balanced with fairness, proportionality, and respect for fundamental rights. This policy represents a dangerous overreach one that sacrifices privacy, chills free expression, and penalizes those who should be celebrated for their global engagement.

If the United States is truly committed to fostering partnerships with countries like Nigeria, it must recognize that sustainable security cannot be built on suspicion and surveillance. Instead, it should embrace and empower the voices of Nigeria’s youth, educated, innovative, and globally connected who could be among America’s strongest allies in the decades ahead.

**Soneye is a seasoned media strategist and former Chief Corporate Communications Officer of NNPC Ltd, known for his sharp political insight, bold journalism, and high-level stakeholder engagement across government, corporate, and international platforms**

OPINION

Dr Emaluji Writes Open Letter To FG, General Public On National Distress

Date: August 6, 2025

OPEN LETTER TO THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AND THE GENERAL PUBLIC

Subject: A Nation in Distress — A Critical Assessment of the Failed Tinubu-Led APC Government

Fellow Nigerians,

As the South-South Volunteer Youth Spokesman of the African Democratic Congress (ADC), I write with a heavy heart and a deep sense of patriotic duty to call attention to the rapid and disturbing collapse of governance under the leadership of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu and the All Progressives Congress (APC). What we are witnessing is not just a national crisis — it is a complete breakdown of systems and values that once gave our country hope.

In every measurable sector of our national life — the economy, security, food security, infrastructure, governance, and social cohesion — this administration has failed woefully. The consequences are no longer abstract statistics; they are lived realities for millions of Nigerians.

1. Poverty and Hunger at Unprecedented Levels

Today, Nigeria holds the tragic record as the poverty capital of the world. Families go entire days without food. Prices of basic food items such as rice, garri, yam, and bread have more than tripled. Hunger is now a weapon, a daily battle for the poor and even the middle class.

2. Hyperinflation and a Crumbling Economy

The naira has lost over 70% of its value in just over a year. With inflation well above 35%, the average Nigerian can no longer afford rent, fuel, transportation, or medical care. Small businesses are shutting down en masse, while unemployment surges. There is no cash in circulation, no confidence in the banking system, and no trust in leadership.

3. Insecurity Across the Nation

From Sokoto to Delta, Borno to Enugu, no region is spared. Banditry, kidnappings, assassinations, ritual killings, and armed robbery are daily news. Our security forces are overwhelmed and underpaid, while leadership at the top offers empty reassurances and photo-ops.

4. Neglect of Contractors and Economic Sabotage

It is both shocking and unacceptable that Federal Government contractors who executed infrastructure and service-based projects for national development have not been paid for over nine months. In June 2025, more than 5,000 local contractors took to the streets in Abuja to protest non-payment. Many of them are now bankrupt. Some have tragically lost their lives due to stress and untreated medical conditions resulting from financial ruin.

Let it be known that these contractors are the backbone of infrastructure and service delivery in Nigeria. When they are denied payment, schools, hospitals, roads, and water systems remain unfinished. Workers are laid off. More Nigerians fall into poverty. The economy suffers — all because this administration refuses to do the bare minimum: honour its obligations.

5. A Government that Refuses to Listen

President Tinubu and the APC have shown zero regard for public opinion, professional advice, or human suffering. Rather than admit failure and course-correct, they weaponize propaganda, distract with divisive rhetoric, and gaslight the nation with false promises.

Our Stand as ADC Youth Volunteers

As youth leaders of the ADC in the South-South and across the country, we reject this incompetence, this deception, and this collapse. The future of Nigeria cannot be mortgaged to leaders who are incapable of managing crises, who reward loyalty over competence, and who treat Nigerians as expendable political pawns.

We call on all well-meaning Nigerians, civil society organizations, religious leaders, and traditional rulers to rise and speak truth to power. The time for silence is over. A new Nigeria cannot emerge from a foundation of betrayal, hunger, and bloodshed.

Enough is Enough.

Signed,

Dr. Emaluji Michael Sunday

South-South Volunteer Youth Spokesman

African Democratic Congress (ADC)

Email: adcvolunteers.ng@gmail.com

Tel: +234 8065667809

-

SPORTS24 hours ago

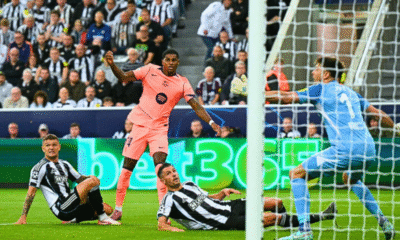

SPORTS24 hours agoBarcelona edge Newcastle 2-1 thanks to Rashford’s Second-Half magic

-

NEWS15 hours ago

NEWS15 hours agoNigerian Born Int’l Journalist, Livinus Chibuike Victor, attempts to attain Interviewing Marathon of 72hours 30 Seconds

-

NEWS15 hours ago

NEWS15 hours agoNSITF mourns Afriland Towers fire VICTIMS, calls for stronger workplace safety

-

NEWS15 hours ago

NEWS15 hours agoSouth East NUJ hosts homecoming, awards Chris Isiguzo Lifetime Achievement Honour

-

NEWS11 hours ago

NEWS11 hours agoJUST-IN: Gov Fubara returns to Port Harcourt as Tinubu ends Emergency Rule

-

NEWS6 hours ago

NEWS6 hours agoForce PRO Benjamin Hundeyin visits NUJ FCT, calls for media collaboration

-

NEWS3 hours ago

NEWS3 hours agoFCT Health Secretary confirms Abuja Ebola-Free

-

NEWS3 hours ago

NEWS3 hours agoGov Fubara addresses Rivers People after Emergency Rule (Full Text)