OPINION

Aminu Tambuwal: Religious Tolerance And The Challenges Of Democratic Governance In Nigeria

INTRODUCTION

It gives me great pleasure to have the privilege of addressing this distinguished audience. I am immensely grateful to the Governing Council, Management and staff of this highly esteemed university for giving me a worthy platform to share my thoughts with you on this auspicious moment of Fountain University’s 4th & 5th Convocation Ceremony.

When I was approached to deliver this Convocation Lecture, I readily agreed, for it is a great honour to be associated with educational endeavours. It is also an opportunity to interact with men and women of integrity and academic excellence. Undoubtedly, the whole of human civilisation was built by intellectuals and other exemplary men and women of wisdom and intellect. Their sustained efforts steer institutions that promote good governance and socio-economic development. In this respect, our highly placed Fountain University, Oshogbo, is certainly a shining example of a citadel of learning that is being driven by the lofty ideals of a reputable religious organisation – Nasrul-Lahi-L-Fatih Society of Nigeria (NASFAT).

In the letter appointing me to serve as the Guest Lecturer at this ceremony, the organisers so benevolently allowed me to choose a topic that touches on issues of interest to our national life. Accordingly, and taking into cognizance the background and foundation of the Fountain University, as well as the prevailing reality of our times, I decided to speak on the topic: “Religious Tolerance and the Challenges of Democratic Governance in Nigeria”.

My choice of this topic is anchored on the conviction that nations just don’t happen by historical accident. Rather, they are built by men and women with vision and high sense of resolute. Building a polity, therefore, entails avowed determination and sacrifice to address the incessant tensions and conflicts, which tend to mar our aspirations for building a united and prosperous nation.

I will initially discuss the challenges of nationhood with which Nigeria has been grappling. The second and third sections dwell on the causes of conflicts in the Nigerian polity, and the potentialities of democracy as a viable tool for good governance, the last section is a modest attempt to propose a way forward towards religious harmony and tolerance in the country. My humble experience as a legislator, a legal practitioner and a politician presiding over the executive affairs of the government of Sokoto State is likely to influence the direction of my lecture. So, bear with me!

The Nigeria Project

The project for the construction of Nigeria’s nationhood commenced with the amalgamation of Northern and Southern Protectorates of the Niger in 1914 and ended with Nigeria’s Independence in 1960. As in all cases of nations across the globe, the challenge has not been one of constituting the nation, but of preserving and sustaining what, in the case of Nigeria, could be said to have been established, fait accompli. Invariably, all nations possess unique challenges in sustaining their nationhood. Some survived, while others could not pass the litmus test. For instance, the United States had to go through a bloody civil war from 1861 – 1865. However, India broke away after its independence of 1947. The issue of Bangladesh is a case in history. The most recent example is what happened or is rather happening to Sudan. Certainly, “it is one thing to construct and secure a nation; it is another to sustain it”, as one scholar recently noted.

The historic amalgamation of Nigeria has often been attributed as the foundation of the rancorous relationship between the two regions of Nigeria. Northern Nigeria consisting of three geopolitical zones with largely Muslim population. It was the centre of a pre-colonial Islamic Empire – the Sokoto Caliphate and its vast Muslim population. Heirs to the Caliphate are inspired by the wider Muslim world, in terms of religious, socio-political and cultural values. The South, an ethnically diverse region, also having three geopolitical zones, is largely Christian. The major socio-political inclination is towards western culture and traditional African heritage. Each of the two Regions have ethnic and religious minority, harbouring their own grievances. These grievances are often expressed through bitter politicking, or sectarian crisis, more or less pauperized by political jobbers and negative media rhetoric.

History has also amply demonstrated that prior to independence, Nigerian nationalist leaders have fully discussed all issues relating to the transition to self-rule. Similarly, there were also interactions after independence on the effect of what is regarded as the arbitrary colonial unification and necessary strategies designed to reconcile differences in aspirations, priorities and vision. However, there were deep and, in some instances, subsisting sentiments because some people saw Nigeria as “the mistake of 1914”, whereas others considered it as “a mere geographic expression”. There were also fears, hopes and anxieties from a wide spectrum of groups in the two regions, even if exaggerated. For instance, Christians do express concerns that “politically dominant Muslims could Islamise national institutions and impose Shari’ah on non-Muslims. Muslims, on the other hand, have the fear of what they regarded as “unbridled westernisation that is antagonising the Islamic belief system”, according to one commentator. The issue, however, is whether the amalgamation was an act of colonial convenience; or even that it was a “mistake”. The reality on the ground is that, for better or for worse, Nigeria is a political entity bounded by a common destiny. So, we need to focus on the fundamental task of nation building.

Nation building is, in itself, a complex task that requires the fixing of so many inter-woven issues. With the attainment of independence, more than five decades ago, the expectation was that Nigeria would emerge as a strong nation, commanding respect among the comity of nations. However, the soaring rise of poverty, unemployment, ethno-religious crisis, poor infrastructure, environmental hazards, insecurity, as well as leadership deficit have conspired to deny the country the advantage to reach the benchmark of development in the 21st century. The phenomena of ethno-religious conflict has plagued and threatened the very existence of the nation owing to the aforementioned factors.

Mismanagement of our resources and misrule by the elites from all corners of the country have been the other major factors, which impoverished and denied opportunities for growth to many Nigerians. Indeed, religious rhetoric blaming members of other religious groups has been appealing among the masses owing largely to their relatively low level of education and awareness. The quest for a religious utopia has given some opportunistic political gladiators the excuse to seek legitimacy by hoodwinking the citizenry via false religious pretentions. Since independence, religious and ethnic rhetoric has leveraged claims to political representation and opportunities. On the other hand, corruption and incompetent leadership have added another dimension to the ugly phenomena in not only preventing equitable distribution of resources and opportunities but also in making the politics of religious and ethnic exclusivity more appealing. The nation, therefore, needs to evolve a system of leadership selection and accountability, which produces the sort of leaders that can confront the challenges associated with our history, socioeconomic inequality, and the establishment of strong institutions for democracy and good governance.

The pertinent questions to ask at this point are: Why is the task of nation building so difficult in Nigeria despite our enormous human and natural resources? What are the challenges and threats associated with nation building? To what extent has leadership confronted these challenges? How do we identify weak political and development institutions with a view to strengthening them?

I share the view of some scholars that the negative effect of colonialism on the development of a nation has been exaggerated. The success of many Asian countries supports this viewpoint. In fact, many of these countries had industrialised and attained enviable levels of development, despite colonial experiences. What Nigerian need is the willpower and determination to succeed in addressing the challenges of the day. In this way, we can aspire to build an illustrious future. Imagine, Malaysia is a major exporter of oil palm and it is from Nigeria that it imports its palm kernels! Haba!!

ETHNO-RELIGIOUS CONFLICTS AND DISHARMONY IN THE NIGERIAN POLITY

With over 400 ethnic groups belonging to several religious sects, Nigeria since independence has remained a multi-ethnic nation State, grappling with the problems of ethno-religious conflicts. Ethnicity and religious intolerance have led to the recurrence of ethno-religious conflicts. Major motivations behind most religious conflicts are economic and political, for, as one scholar puts it: “in the struggle for political power to retain the monopoly of economic control… the political class instigates the ordinary citizen into mutual suspicions resulting in conflicts”.

This is not to underplay other factors, such as ways of propagating religions, mistrust and suspicion between followers of various religions and ethnic groups, selfishness and illiteracy. Religion can indeed serve as an instrument of social cohesion, but it can also spur adherents towards violent acts. Hence, its description as a “double-edged sword” by some public policy analysts.

The fact is that colonialism did not cause the primordial conditions that generated conflicts between Christians and Muslims, but it made them worse. Indeed, colonialism established the basis for using identity politics as a means of accessing political and economic resources. Consequently, religious differences come to worsen political crisis. From the early 1980s, religion has been making increasing in-road into the political development of Nigeria, in spite of the official legal status of the country as a secular state. This is a status accepted by the majority of Nigerians, and it is clearly laid down in the constitution.

Nigeria is at the moment experiencing major challenges. It is one of the fastest growing nations with a population that doubles every two and a half decades. Access to higher education and healthcare is limited. Poor infrastructure and weak leadership deficit have also conspired to impede the development of the country.

Notwithstanding this perception, it is important to attempt an objective assessment of the role of religion in the task of nation building in such a way that it will be a unifying factor rather than a divisive one. The spate and magnitude of the crises caused by religious disharmony has been captured by NEMA in its 2015 Annual Report, thus:

In 2014, insurgency, communal clashes, floods, windstorms and fire were primarily the main causes of people’s displacement, physical damages and loss of lives in the country. The Northeast and North Central parts of the country had more human induced emergency situations than any other part. The others experienced more of natural causes. Insurgency caused more havoc that affected more population and obstructed the normal functioning of local economic activities in the affected areas.

Obviously, religious intolerance in itself is the outcome of the way and manner that religious education is taught in various religious groups. This is especially glaring in terms of insurgency, which is, for the most part, caused by poor education or the lack of it and religious bigotry. However, all factors as mentioned have been amplified by Nation’s conspicuous challenges to do with unemployment, poverty, and leadership deficit.

It is pertinent to state that the Nigerian Constitution has evidently created a balance of power between all religions, so as to make it difficult for any religion to realise the dream of becoming dominant. There is, therefore, the need to cultivate tolerance and co-operation that will promote peaceful co-existence. However, the balance tends to provoke tendencies for confrontation leading to religious conflicts capable of derailing our democratic culture and unity of the country. Causes of disharmony or conflicts amongst religious groups in the country, as variously propounded include:

i. Conflicts or misunderstanding fuelled by socio-political, economic and governance factors

ii. Disharmony facilitated by Government’s neglect, oppression, domination, and related discriminatory processes

iii. Conflicts and disharmony aggravated by the weak nature of State institutions.

iv. Conflicts and disharmony provoked by, for example, disparaging publications,

vilification of other people’s views, values, wrong perception of other people’s faith.

v. Conflicts essentially triggered by religious intolerance, fundamentalism and extremism, which are mostly caused by poor education or lack of it.

Seen in this context, there is a need to put religion in its proper perspective in the nation’s building process. Indeed, religion has been made to be both an emotional and explosive issue in Nigeria. The scenario could create problems too serious to solve. The civil war of 1967-1970 was largely fought for political, economic and ethnic reasons. The nation survived it mainly because it was hardly a religious war. However, religious grip is growing firmer and increasingly determining the politics and culture of Nigerians in all walks of life.

Some writers are of the view that “nothing has threatened Nigeria’s nationhood more than religion”, I would, however, argue that it is the narrow interpretation or misinterpretation of religion that has been the problem. This narrow interpretation in the context of Nigeria’s politics has created the basis of tension in the struggle by religious groups to assert superiority and dominance in the socio-economic and political spheres. While the Nigerian constitution has taken steps to moderate the excesses, the gap as to whether Nigeria is a secular state or a pluralist one has to be resolved. I, for one, do not go along with the contestation as to the possibility of the State being neutral in the religiosity of its people. In my view, the illiteracy factor is the most potent variable, which should be controlled. This is obvious, as we are quite aware of the enormous contributions being rendered by religious organisations, such as NASFAT, in the educational development of this country.

Records abound on the considerable role of Muslim Organisations to the development of education, peace and unity of this country. Some of these include Ansaruddeen Society (established in Lagos in 1923), Anwaruddeen Society established in Abeokuta in 1939, the Ansarul-Islam Society of Nigeria established in Ilorin in 1943, the Muslim Students Society of Nigeria established in Lagos in 1954 and indeed, the Jama’atul Nasril Islam, with its Headquarters in Kaduna, and established in 1962.

Through the activities of these organisations, Muslims were given basic training, which empower them to contribute to the manpower development of Nigeria. In fact, it has been contended by scholars, such as Prof Balogun, that “the problem of imbalance between the quantity and the quality of personnel in the public sector would have been more acute” if not for the opportunities provided by these organisations for the acquisition of western education within a congenial Islamic atmosphere.

The glaring contribution of NASFAT in this regard, hardly needs to be mentioned. NASFAT’s presence and conspicuous contributions in the dissemination of orthodox religious values amongst all Muslims in all parts of the country is so obvious to require explanation. There are also other Islamic organisations in the modern times such as the Qadiriyya and Tijjaniya Sufi orders; Jama’atul Izalatul Bidi’a Wa’ikamatus Sunnah, National Council of Muslims Youth Organisation, Muslim Students Society of Nigeria, Federation of Muslim Women Association in Nigeria, that are working concertedly to prove that Islamic civilisation is not a perversion of its distortion designed by unfortunate forces causing conflicts, violence or insurgency of any type. The organisations are also working round the clock to orient the Muslim Ummah to embrace the true tenets of Islam within the context of prevailing ethno-religious reality of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. The formation of the Nigerian Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs in 1974 and its various programmes and activities thereafter abundantly proved that Muslims could effectively discharge their religious duties within the context of a multi-religious nation.

On the other hand, the role of the early Christian missionaries in fostering Nigerian nationalism is very clear. Certainly, the colonial era in Nigeria was one that witnessed a significant and extensive growth in Christian evangelism. Over the years, organisations that helped in bringing all Christians together to promote unity such as CCN, was founded. In August 1976, the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) was formed under the auspices of both Catholic Church and the Protestant Churches, with the “aim of promoting understanding among the various people and strata of the Nigerian Society, and above all, to propagate the Gospel”. Many scholars have written extensively on the contribution of Christianity to nation building, especially in the areas of education and healthcare delivery.

Forces of non-integration of the Nigerian people may have had roots in colonialism, but it is important to understand that societies cannot be parochial localities – autonomous unto themselves. Inevitably, they have to interact with others, to exchange ideas, goods and services. Religious organisations of all divides must be conscious of this fact, and must endeavour to educate adherents, especially those vying for political power to imbibe the virtue and sanctity of human dignity, freedom of will and tolerance.

The phrase “supposing we are all created equal like office pins”, as once thoughtfully raised by Ahmad Deedat, is full of wisdom. God has given the human race the liberty to choose, and as such, it will be sheer naivety for anybody to imagine that he can compel people to follow his own chosen faith. Indeed, what is required is concerted effort to rise against moral decadence, illiteracy and spiritual bankruptcy, which are fanning the embers of religious intolerance and conflicts.

DEMOCRACY AND GOOD GOVERNANCE

It is a popular consensus in modern times that democracy has the highest capacity and potential for propelling good governance. In fact, the task of evolving an enduring and all-inclusive sustainable political culture that will guarantee freedom and opportunities to all is the cornerstone of democratic governance. The majority of Nigerians have confidence that the myriad of problems and challenges facing the nation are surmountable if only a truly democratic government is operated in the country.

Central to democratic governance, as it is well known, is the respect for rule of law, fundamental human rights, freedom of expression, separation of powers, fairness and equity, as well as the strengthening of institutions for effective service delivery.

The problems of ethnicity and diversity can actually be blended to be a source of strength under democratic governance. Undoubtedly, citizens of this country, belonging to different races, tribes and religions are united together by common history, nay destiny. Democracy, on the other hand, has the capacity of effecting the desired integration. In this regard, we can craft an enduring political system that effectively counters disharmony and intolerance under the democratic culture. The essential ingredients, to my mind, are as follows:

i. Prevalence of peace and security

ii. A leadership that is genuine in its intention and nationalistic in outlook

iii. Provision of an enabling environment for wealth creation

iv. Provision of equal opportunity to all ethnic and religious groups, which will enable them to participate actively in the governance of their country

Let me stress, at the risk of sounding obscure, that beyond the question of amalgamation lies the survival of the Nigerian State, because this is the reality on the ground. We need to fully understand the forces working to derail all efforts aimed at nation building. Knowledge of the historical links and appreciation of socio-political values within the democratic system of government must, therefore, be clearly delineated.

For instance, prior to British colonial rule, Islam had already become well established in Nigeria, with the exception of Igboland and Niger Delta, manifesting itself as a religious creed, a political force, a legal system, as well as an intellectual and cultural tradition. In fact, Islam has enjoyed the status of a state religion in all parts of northern Nigeria in the 19th Century. It is, therefore, necessary to understand that there is varying conceptual understanding of the role of religion in different parts of the Nigerian polity.

It is the duty of politicians and leaders to establish standards of governance, by using different tactics or strategies. Unity of purpose, patriotism and selflessness are, in this regard, most crucial for building a dynamic democratic culture that will ensure the integration of all ethnic and religious groups on the basis of fairness and justice.

Sir Ahmadu Bello, Sardaunan Sokoto, and indeed other founding fathers worked assiduously to ensure that ethnic chauvinism and religious bigotry found no place in the political process. In fact, the depth of integration amongst ethnic and religious groups in northern Nigeria in the 1960s has continued to resonate until today.

The consensus, then, is that the nation’s route to sustainable development is democracy. Building a democratic culture that is capable of achieving the objective of national integration, in my view, is contingent on the following hard truths:

i. The executive arm of government should not encroach on the duties and responsibilities of the legislature and judiciary.

ii. The legislature must endeavour, at all times, to undertake its oversight functions, selflessly and patriotically.

iii. The judiciary must show probity and be assertive in jealously guarding its integrity, by ensuring that justice is done to all without fear or favour.

iv. Public and political office holders, at all levels, must adhere to constitutional stipulations, and ensure responsible and accountable governance.

v. The Public Service is in need of restructuring and reform, guided by integrity and merit, thereby engendering global best practice in everyday operation of all ministries, departments and agencies of government.

No doubt, challenges of democratic governance do manifest themselves in different outfits. The most critical of these challenges, however, is in the context where misguided criticisms, negative politicking, eccentric or bigoted preaching are used as instruments of destabilisation.

Certainly, our experience with democracy in Nigeria has amply demonstrated that true democrats can effectively address issues of socio-economic inequality, promote access to basic education, health and housing. It can also help us to find ways of curbing ethnocentric exuberance and religious bigotry.

SOLUTIONS TO RELIGIOUS INTOLERANCE

It is obvious, that religious and ethnic rhetoric have been used as a cover to claim political representation and opportunities. Invariably, most politicians could hold at anything in the struggle for power, damning the consequences. In this regard, political differences have ignited many sectarian crises. It is therefore essential to free religion from the grief of dark forces – either as charlatans, religious bigots or unfortunate political jobbers.

Controlling religious intolerance in this country has to ensure that causes of disharmony are squarely addressed. In my view, the democratic system of government could undertake this exercise. However, in this undertaking, the capacity of democratic institutions must be strengthened to ensure that unpatriotic and mediocre politicians are cleared out.

The task primarily involves the laying of a solid foundation for a democratic culture, whose operators are fair to all irrespective of their circumstances.

In essence, politicians, public officials and political office holders must be those who are not necessarily detached from religion, but who have the understanding that religion is in itself a tool for peace, progress and sustainable development. Such leaders would work to address the challenges of our history, the challenges of socio-economic inequalities, and indeed, the challenges of building vibrant and strong institutions for democracy and sustainable development.

To ensure that religion plays its vital role as a source of harmony, truth and hope for the nation within the prevailing democratic culture, I proffer the following suggestions:

i. Exposing and penalising all divisive agents of violence and lawlessness, within the purview of existing laws. Leaders, law enforcement agents and traditional rulers have a concerted role to play in this regard.

ii. Sincere and open discussions and dialogue amongst religious groups and organisations. JNI, NSCIA, CAN, leaders, security agencies and traditional rulers at all tiers of government will need to constantly discuss areas of interests, agreements and disagreement with a view to promoting unity and understanding.

iii. Mounting robust enlightenment programmes that would foster inter-faith understanding. The tremendous achievements recorded by Nigeria Inter-Religious Council (NIREC) need to be consolidated by finding more strategies that would promote its envisaged objectives.

iv. The need to control the many factors that are impacting directly or indirectly bearing on religious disharmony such as unemployment, poverty, inadequate security, depletion of cultural values, unhindered movement of persons along the frontiers and more conspicuously – bad politicking.

v. The need to discouraged disparaging publications and negative utterances by scholars and unpatriotic media practitioners.

vi. The recurring need for religious organisations to embark on rigorous educational training and the enlightenment of adherents as exemplified by JNI, NASFAT and other orthodox religious groups.

vii. The enlightenment of the general populace to differentiate between true democrats who are in politics for the development of fatherland and those who are in politics for their selfish aggrandisement.

viii. The need for the citizenry to be proactive in promoting good governance and fighting corruption and bad leadership within the limits of the law.

CONCLUSION

Distinguished audience, let me, in conclusion reiterate the point that ethnic and religious harmony has been exemplary in the history of Nigerian polity. Disputes and conflicts witnessed over the years in Nigeria have been more or less caused by poor education or lack of it among our people, who are mostly hoodwinked by unpatriotic persons seeking to advance their self-interest. These unpatriotic citizens are to be found mostly in the corridors of political and economic power.

Democracy, being a system, which gives freedom to people more than any other system of government, is open to abuse by unpatriotic citizens for their own narrow interests. However, I have argued throughout this lecture that democratic governance could effectively solve the problems of religious intolerance through the election of politicians of high calibre, who are patriotic, selfless and people-oriented.

A people-oriented system of government will, then, have the capacity of understanding our differences and inspiring all groups to contribute to nation building, without losing their identity. It is my ardent hope that my lecture will elicit further discussions on the subject.

Thank you.

—————————-

This is a convocation lecture delivered at Fountain University, Osogbo by Governor of Sokoto state, Aminu Waziri Tambuwal on Monday, November 28, 2016.

OPINION

Enhancing Workplace Safety And Social Protection: The Role Of The Employees’ Compensation Act, 2010

Presentation by

Barr. Oluwaseun M. Faleye

Managing Director/Chief Executive, Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund

At the 65th Annual General Conference of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA)

International Conference Centre, Enugu

24th August 2025

Introduction

Distinguished colleagues, esteemed members of the Bench and Bar, fellow policymakers, captains of industry, and ladies and gentlemen.

It is both an honour and a privilege to stand before this distinguished assembly at the 65th Annual General Conference of the Nigerian Bar Association. The NBA has, over decades, remained the conscience of our nation, a defender of rights, a champion of justice, and a custodian of the democratic ideals that gives meaning to our collective existence.

The theme of this year’s conference, “Stand Out, Stand Tall!” is more than a slogan. It is a call to courage, to excellence, and to visionary leadership. It challenges us, as thought-leaders and nation-builders, to lift our society beyond mediocrity and to confront the existential issues that hinder Nigeria’s march toward greatness.

I stand today to speak directly to one of those existential issues, the safety of our workplaces and the social protection of our workers. These are not peripheral concerns; they touch the very core of our humanity, our economy, and our pursuit of sustainable national development.

In focusing on “Enhancing Workplace Safety and Social Protection: The Role of the Employees’ Compensation Act, 2010,” I aim to situate our conversation at the intersection of law, labour, and human dignity.

Work is not merely an economic activity; it is central to human identity and social progress. Through work, families are sustained, communities are developed, and nations are built. The dignity of labour, so deeply rooted in our cultural and constitutional ethos, affirms that every worker deserves protection, not just in the fruit of their labour, but also in the very process of labouring.

Yet, the paradox remains: while work empowers, it can also endanger. The same factories that generate wealth can expose workers to industrial hazards; the same oil rigs that earn foreign exchange can subject workers to occupational illnesses; the same construction sites that build our cities can also claim lives in accidents.

This paradox highlights the urgency of workplace safety and the necessity of social protection. It is not enough for a nation to pursue economic growth; such growth must be inclusive, humane, and protective of those whose sweat oils the engines of development.

The Global Context: Grim Realities of Workplace Hazards

Permit me to share with you the grim realities of workplace hazards, and these statistics are not mine; they were provided by the International Labour Organization:

Each year, over 2.8 million workers die from occupational accidents and work-related diseases.

Over 374 million workers suffer non-fatal injuries annually, many of which lead to long-term disabilities or reduced quality of life.

The economic cost of poor occupational safety and health is estimated at nearly 4% of global GDP annually, a staggering burden on productivity, healthcare systems, and social welfare.

These statistics are not just numbers; they are human lives, families disrupted, and dreams shattered. They remind us that workplace safety is not a privilege to be enjoyed by a few but a right owed to all.

Within the context of our own country, our peculiar socio-economic realities make workplace safety and social protection even more urgent.

Data Gaps: Accurate national data on workplace accidents remains limited. However, the Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund, through its Employees’ Compensation Scheme, continues to receive increasing claims from affected workers and employers.

High-Risk Sectors: Industries such as construction, oil and gas, and manufacturing remain prone to frequent and sometimes fatal workplace accidents. Poor adherence to safety standards, inadequate enforcement, and limited awareness exacerbate the problem.

Informal economy Vulnerability: With over 80% of Nigeria’s workforce engaged in the informal economy, millions of workers remain outside structured occupational safety nets, leaving them and their families highly vulnerable in the event of accidents or diseases.

Cultural and Institutional Weaknesses: In many workplaces, safety culture is weak. Employers often see safety compliance as a cost rather than an investment, while workers themselves may lack training or incentives to prioritize safety.

The outcome of these realities is clear: rising workplace accidents, preventable occupational illnesses, and increasing claims for compensation. More importantly, the loss of human capital undermines national productivity and deepens poverty traps for affected families.

Why Workplace Safety and Social Protection Matter

Workplace safety and social protection are not optional luxuries; they are fundamental pillars of social justice, human dignity, and economic sustainability.

They ensure dignity, peace of mind, and assurance that one’s labour will not become a source of tragedy for one’s family.

They enhance productivity, reduce downtime due to accidents, and foster industrial harmony.

They reduce the burden on healthcare systems, mitigate poverty, and enhance national competitiveness.

In essence, workplace safety and social protection are as much about human rights as they are about economic development. A nation that fails to protect its workers fails to protect its future.

The Employees’ Compensation Act, 2010: A Paradigm Shift

The enactment of the Employees’ Compensation Act (ECA), 2010 marked a watershed moment in Nigeria’s labour and social security landscape. It replaced the Workmen’s Compensation Act, a law that had long been criticized for its narrow scope, rigidity, and employer-centric bias.

For decades, Nigerian workers and their families bore the brunt of a compensation system that failed to adequately recognize the evolving realities of modern workplaces. The law operated within the framework of an industrial era that no longer reflected the complex dynamics of contemporary employment relationships. Workers were often left destitute after workplace accidents, while employers faced prolonged litigation that neither restored the injured nor secured industrial harmony.

The ECA 2010 emerged as both a legal reform and a moral commitment, aligning Nigeria with international best practices, especially as recommended by the International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions on occupational safety, health, and social security.

1. Comprehensive Coverage

One of the most remarkable contributions of the ECA is its expansive scope.

It applies to all employers and employees across both the public and private sectors, creating a unified national standard.

It extends protection beyond physical accidents to include:

Occupational injuries sustained in the course of work.

Occupational diseases arising from exposure to harmful substances or hazardous environments.

Permanent and temporary disabilities, whether partial or total.

Mental health challenges linked to workplace stress, trauma, or hazards, an innovative inclusion that reflects global recognition of psychosocial risks.

By broadening its ambit, the ECA acknowledges the complex and evolving nature of work, ensuring that no worker is left behind simply because their injury or illness does not fit into a narrow definition.

2. Employer Contribution System

The ECA dismantled the inequitable structure of the past where individual employers bore sole liability for compensation. Under the Workmen’s Compensation Act, an employer had to directly compensate an injured worker, often leading to disputes, prolonged court cases, and financial strain.

In contrast, the ECA introduced a collective, pooled system where employers across sectors contribute to a central fund administered by the Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund. The Fund ensures that resources are available upfront to address claims promptly, rather than waiting for the outcome of litigation.

The pooled risk model reflects the principle of social solidarity, spreading risks and costs across the economy, rather than isolating them within a single workplace.

This mechanism not only secures workers’ rights but also protects employers from the unpredictability of individual liability. It shifts the focus from blame to shared responsibility.

3. Quick and Fair Compensation

The ECA was deliberately designed to speed up and humanize the compensation process.

Injured workers are entitled to immediate medical treatment without the burden of proving employer negligence. Beyond treatment, workers receive physical rehabilitation, vocational training, and support for reintegration into the workforce.

In cases of permanent or temporary disability, the law guarantees structured financial support. Dependents of workers who lose their lives in workplace accidents receive death benefits, ensuring families are not plunged into poverty.

This no-fault principle, where workers are compensated regardless of negligence, removes the adversarial tension of litigation. It prioritizes healing, dignity, and security over legal wrangling.

4. The Social Security Dimension

Perhaps the most transformative feature of the ECA is its broad social security orientation. Unlike its predecessor, the Act is not limited to post-accident compensation but also embraces prevention, rehabilitation, and reintegration.

5. A Balance between Rights and Responsibilities

The genius of the Employees’ Compensation Act lies in its balance.

For workers, it guarantees protection without the hurdles of litigation or the uncertainty of employer discretion. For employers, it eliminates the risk of crippling lawsuits and provides predictable contributions into a shared pool. For the nation, it strengthens social justice, reduces systemic poverty traps, and aligns Nigeria with international labour standards.

Thus, the ECA 2010 represents more than just legal reform, it is a paradigm shift towards a modern, inclusive, and humane labour ecosystem. It affirms that in Nigeria’s pursuit of growth, the lives and dignity of workers cannot be treated as expendable.

Current Realities and Challenges

Fifteen years after its enactment, the Employees’ Compensation Act 2010 has undoubtedly transformed Nigeria’s labour compensation framework. The establishment of a no-fault, pooled compensation system has brought hope to thousands of workers and their families. Yet, as with most legal and policy reforms, the journey from law on paper to lived reality has been uneven.

While progress has been recorded in claims processing, accident coverage, and legal clarity, several persistent and emerging challenges continue to undermine the Act’s full impact.

Low Employer Compliance

One of the most pressing realities is incomplete employer compliance, especially among Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs).

Despite being the backbone of Nigeria’s economy, accounting for over 80% of jobs and nearly 50% of GDP, many SMEs either fail to register with the NSITF or under-declare their workforce size and wage bills.

Reasons for non-compliance include limited awareness of legal obligations, perceived cost burden of contributions and weak enforcement and monitoring mechanisms.

The result is that millions of workers in SMEs remain outside the protective umbrella of the Act, leaving them vulnerable to poverty traps in cases of workplace accidents.

This compliance gap undermines the spirit of universality and inclusivity envisioned by the law.

Limited Awareness Among Workers and Employers

A large proportion of Nigerian employees remain unaware of their rights under the Act.

Many workers do not know they are entitled to compensation in cases of occupational injury or disease. In some cases, employers exploit this ignorance by discouraging claims or providing token settlements instead of due benefits.

Even among educated workers, there is often confusion between ECA entitlements and other social protection schemes like pensions or health insurance.

Awareness campaigns have been sporadic, with limited penetration outside major cities. For a country with over 70 million workers in the informal and formal sectors combined, sustained national enlightenment is essential and we are committed to doing that to ensure that Nigerian workers understand their rights and the benefits associated with complying with the Employee’s Compensation Act.

Under-Reporting of Workplace Accidents

Another major challenge is the systemic under-reporting of workplace accidents and occupational diseases.

Many employers fear that reporting incidents will attract sanctions, regulatory scrutiny, or reputational damage.

Workers themselves sometimes avoid reporting for fear of losing their jobs, stigmatization, or bureaucratic delays in accessing benefits. This results in a data gap, making it difficult for policymakers and regulators to accurately assess the scope of occupational risks in Nigeria.

For instance, while the International Labour Organization estimates that 2.8 million workers die globally every year from work-related causes, Nigeria’s official records capture only a fraction of actual cases. The absence of reliable, comprehensive data limits the country’s ability to design targeted interventions.

Changing Work Dynamics in a New Economy

The world of work is changing rapidly, and Nigeria is no exception. The ECA 2010, while progressive, must continuously adapt to these evolving realities.

Platforms like ride-hailing services, delivery apps, and freelance digital work create new categories of workers who often fall outside traditional employer-employee relationships.

As I have mentioned, over 80% of Nigerian workers operate in the informal economy, where workplace safety standards are often non-existent. Extending the ECA’s protections to this vast segment remains a daunting but necessary task.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated remote work adoption, raising new questions about what qualifies as a “workplace accident” when work is performed from home.

With automation, robotics, and artificial intelligence entering workplaces, new categories of hazards, such as ergonomic injuries, mental stress, or even cyber-related risks are emerging.

These shifts demand dynamic legal interpretation and possible amendments to ensure that the ECA remains relevant in a rapidly changing labour market.

These realities highlight the need for multi-sector collaboration, linking labour law enforcement with broader economic reforms, social welfare, and national development strategies.

The Role of Lawyers and Policymakers

The implementation and impact of the Employees’ Compensation Act, 2010 cannot rest on the NSITF alone. Like every piece of transformative legislation, the ECA lives and breathes through the interpretation, advocacy, and enforcement carried out by lawyers, judges, and policymakers.

Apart from our expectation of you as advocates of the efficacy and importance of the Employees’ Compensation Scheme, the most crucial expectation we have of you lawyers and leaders of the bar here is to lead by example.

We must comply with the law ourselves. We must ensure that all law firms practicing law in Nigeria subscribe to the Employees’ Compensation Scheme.

As you all know, law practice, particularly those of our colleagues engaged in dispute resolution practices comes with its risks. Lawyers travel to different parts of this country practicing their trade, advocating and defending clients. These journeys come with risk.

For the corporate and commercial lawyers, they tend to sit for hours reviewing documents, negotiating agreements and also do a lot of traveling in the course of work. These long hours at work stations often leads back and spinal injuries.

Indeed, the pressure of work could sometimes lead not only to physical challenges but to mental stress as well. Yet, majority of our law firms are not complying with the Employees’ Compensation Scheme to give their employees, fellow lawyers the safety net the law prescribed and which they all deserve.

The NBA must do more and ensure that all law firms comply with the Employees’ Compensation Act to safeguard our workforce. And it is my hope that the Welfare Committee of the NBA will champion this initative.

We must ensure that evidence of compliance with the ECA becomes part of documentation for aspiring to be Senior Advocates. As part of the law firm inspection exercise towards the conferment of silk, I urge us to ask for evidence that law firms are complying with the Employees’ Compensation Act akin to our position on payment of pension obligations for lawyers.

Corporate lawyers are often the first point of contact for businesses seeking to understand their obligations under labour laws. It is therefore incumbent on them to educate employers, particularly SMEs on the necessity of compliance with the ECA, not only as a legal requirement but as a strategic business investment.

When disputes arise, lawyers must uphold the spirit of social justice embedded in the Act, ensuring that compensation claims are pursued diligently and without undue delay.

Beyond individual cases, the legal community must serve as advocates of systemic reform, engaging with government and civil society to strengthen workplace safety and employee protections.

The Nigerian Bar Association can serve as a bridge between policymakers and the workforce, ensuring that the law keeps pace with global best practices and local realities.

As to the role of the judiciary, we acknowledge that the courts play a pivotal role in giving life to the Act. Therefore, judicial interpretation must consistently reflect the protective, worker-centred philosophy of the ECA.

Landmark rulings can set precedents that discourage employers from evading responsibilities and embolden employees to seek justice without fear.

The judiciary must guard against narrow, technical interpretations that undermine the law’s purpose. Instead, it must elevate the principle that the protection of human dignity is paramount.

From the legislative perspective, our law makers must recognize that the labour market is evolving faster than ever before. Regular amendments to the ECA 2010, whether to address the gig economy, informal economy realities, or technological hazards, are necessary to maintain its relevance.

The ECA 2010, therefore, should not be viewed solely as a labour statute, but as a human rights instrument, a guarantee that every Nigerian worker deserves protection, dignity, and a safety net against the uncertainties of life.

The Future of Workplace Safety and Social Protection in Nigeria

Looking forward, the NSITF’s vision is to build a comprehensive social security architecture for Nigeria, with the ECA as its cornerstone. The Act laid the foundation, but the building of a resilient, inclusive, and future-ready system requires bold innovations.

The Fund is embracing technology-driven solutions to improve speed, transparency, and accountability.

Real-time reporting systems will allow employers and workers to instantly report accidents through digital platforms, ensuring quicker responses. Data analytics will enable predictive modelling, identify high-risk sectors and help prevent accidents before they happen.

E-certificates of compliance which we have already introduced, are reducing fraud and making compliance verification seamless.

The ECS’s future lies in creating innovative schemes tailored to suit the informal economy. Pilot projects are already exploring contributory micro-schemes that will allow even low-income workers to enjoy compensation and protection.

Extending coverage to the informal economy is not only a matter of justice but also of national productivity, since these workers drive much of Nigeria’s growth.

Compensation after injury is important, but prevention is better, cheaper, and more sustainable. The Fund is investing in workplace safety audits to identify risks early, we are undertaking compliance inspections with deterrent sanctions for violators and enhancing our capacity through programs, training employers and employees on global best practices in occupational safety and health (OSH).

By fostering a culture of prevention, Nigeria can reduce workplace accidents and improve productivity across sectors.

Nigeria must continue to harmonize with international standards by ratifying and implementing relevant ILO conventions on occupational safety and health. We must learn from other countries with mature compensation frameworks and systems.

We must leverage partnerships with global organizations to build capacity, fund safety initiatives, and modernize systems. These sorts of global alignment ensures that Nigerian workers are not left behind in an increasingly interconnected labour market.

Conclusion

Distinguished colleagues, learned friends, ladies and gentlemen, the Employees’ Compensation Act, 2010 is more than a statute on the books. It is a covenant of dignity, a shield of protection, and a beacon of social justice for the Nigerian worker.

It represents a promise, that when a worker is injured, they will not be abandoned; when a family loses its breadwinner, they will not be thrown into despair; and when an employer invests in safety, they will be rewarded with loyalty, productivity, and peace.

To truly “Stand Out, Stand Tall,” as this conference theme challenges us, we must rise above rhetoric and build a society where no worker leaves home in fear that their daily bread could cost them their life, no child is forced out of school because an injured parent can no longer provide and no widow or widower is left destitute because justice was delayed or denied.

This is not just about labour law, it is about the soul of our nation. A society that protects its workers protects its future. A nation that neglects its workforce undermines its destiny.

The call before us today is clear.

Lawyers must be the vanguard of compliance and justice, using their knowledge to protect the vulnerable.

Policymakers must be visionaries, ensuring that our laws evolve with the realities of modern work.

Employers must see safety and social protection not as costs, but as investments in their people and their productivity.

And institutions like the NSITF must continue to lead with innovation, transparency, and courage.

If we do this, we will build more than safe workplaces, we will build a safer Nigeria. We will do more than compensate accidents, we will prevent them. We will not just write laws; we will write legacies.

Together, we can build a Nigeria where every citizen can stand out in excellence and stand tall in dignity.

Thank you.

May God bless our workers.

May God bless the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Oluwaseun Faleye

Managing Director/CE

Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund

OPINION

US Visa Applicants And Social Media Disclosure: A Risky Overreach With Dire Consequences For Nigerians

By Olufemi Soneye

The United States has recently implemented a sweeping immigration policy requiring nearly all visa applicants to disclose their social media handles and digital histories. Framed as a tool to bolster national security, counter terrorism, and curb cybercrime, the measure may appear reasonable on paper. But for Nigerians and many others from countries with vibrant, digitally active populations the consequences are troubling and far-reaching.

Nigeria’s dynamic online culture is marked by satire, political commentary, and spirited debate. In this context, posts that are humorous or culturally specific may be misunderstood by foreign officials unfamiliar with the nuances of local discourse. What may be a harmless meme or satirical remark in Nigeria could be wrongly interpreted as extremist, subversive, or fraudulent by US immigration authorities.

This does not merely pose a risk to individual visa applicants. It threatens broader societal values such as freedom of expression, cultural authenticity, and civic engagement. It also risks further straining US–Nigeria relations at a time when collaboration and mutual respect are more important than ever.

The US government maintains that social media activity provides valuable insight into a visa applicant’s character, affiliations, and potential risks. In an age where radicalization and misinformation can proliferate online, there is some logic to this argument. However, in practice, it opens the door to arbitrary interpretations, biased judgments, and significant invasions of privacy.

Disturbing cases have already emerged. A Norwegian tourist was recently denied entry into the United States after officials discovered a meme referencing US Vice President J.D. Vance on his phone. In another case, a Nigerian businesswoman with a valid visa was turned away at a US border after immigration officers reviewed her Instagram messages and claimed her online activity contradicted the nature of her visa. These examples illustrate how subjective and potentially discriminatory the enforcement of this policy can be.

Adding to the concern, the US has launched a pilot program requiring visa applicants from select countries to pay a $15,000 bond. The initiative, which began with Malawi and Zambia, reportedly targets nations with high visa overstay rates and could be expanded. It sends a chilling message: that citizens of certain countries are presumed guilty until proven otherwise.

For Nigerians, the implications are especially severe. Privacy is the first casualty. Applicants must now submit their digital footprints including personal conversations, private networks, and online affiliations to a foreign government. Freedom of expression is the next victim. Young Nigerians, who make up the majority of users on platforms like X (formerly Twitter), TikTok, and Instagram, may begin self-censoring out of fear that political opinions or cultural commentary could jeopardize their chances of traveling or studying abroad.

This policy disproportionately impacts the very demographic that is driving Nigeria’s innovation, creativity, and international reputation. Students, entrepreneurs, artists, and professionals, the most globally engaged Nigerians are now the most vulnerable to misinterpretation and arbitrary visa denials. What constitutes a “red flag” is alarmingly subjective: a meme, a retweet, or a political statement could be enough to trigger rejection, with little recourse for appeal.

There are broader implications for the Nigerian diaspora and global mobility. Social media has long served as a bridge connecting Nigerians abroad with their homeland, facilitating civic dialogue, cultural exchange, and philanthropic engagement. If digital expression becomes a liability, this bridge may weaken, silencing a vital global voice and undermining transnational ties.

Moreover, the policy risks reinforcing damaging stereotypes. Nigerians already contend with international biases linking the country to fraud or instability. A policy that scrutinizes their digital lives under a security lens could deepen mistrust, alienate young professionals, and diminish goodwill toward the United States.

The global repercussions are also concerning. If the US, a global standard-setter in immigration policy, normalizes the collection and evaluation of applicants’ private digital histories, other countries may follow suit. This would set a dangerous precedent, where opportunities for global mobility depend not on merit or intent, but on an algorithmic analysis of social media behavior often devoid of cultural context.

National security is undeniably important. But it must be balanced with fairness, proportionality, and respect for fundamental rights. This policy represents a dangerous overreach one that sacrifices privacy, chills free expression, and penalizes those who should be celebrated for their global engagement.

If the United States is truly committed to fostering partnerships with countries like Nigeria, it must recognize that sustainable security cannot be built on suspicion and surveillance. Instead, it should embrace and empower the voices of Nigeria’s youth, educated, innovative, and globally connected who could be among America’s strongest allies in the decades ahead.

**Soneye is a seasoned media strategist and former Chief Corporate Communications Officer of NNPC Ltd, known for his sharp political insight, bold journalism, and high-level stakeholder engagement across government, corporate, and international platforms**

OPINION

Dr Emaluji Writes Open Letter To FG, General Public On National Distress

Date: August 6, 2025

OPEN LETTER TO THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AND THE GENERAL PUBLIC

Subject: A Nation in Distress — A Critical Assessment of the Failed Tinubu-Led APC Government

Fellow Nigerians,

As the South-South Volunteer Youth Spokesman of the African Democratic Congress (ADC), I write with a heavy heart and a deep sense of patriotic duty to call attention to the rapid and disturbing collapse of governance under the leadership of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu and the All Progressives Congress (APC). What we are witnessing is not just a national crisis — it is a complete breakdown of systems and values that once gave our country hope.

In every measurable sector of our national life — the economy, security, food security, infrastructure, governance, and social cohesion — this administration has failed woefully. The consequences are no longer abstract statistics; they are lived realities for millions of Nigerians.

1. Poverty and Hunger at Unprecedented Levels

Today, Nigeria holds the tragic record as the poverty capital of the world. Families go entire days without food. Prices of basic food items such as rice, garri, yam, and bread have more than tripled. Hunger is now a weapon, a daily battle for the poor and even the middle class.

2. Hyperinflation and a Crumbling Economy

The naira has lost over 70% of its value in just over a year. With inflation well above 35%, the average Nigerian can no longer afford rent, fuel, transportation, or medical care. Small businesses are shutting down en masse, while unemployment surges. There is no cash in circulation, no confidence in the banking system, and no trust in leadership.

3. Insecurity Across the Nation

From Sokoto to Delta, Borno to Enugu, no region is spared. Banditry, kidnappings, assassinations, ritual killings, and armed robbery are daily news. Our security forces are overwhelmed and underpaid, while leadership at the top offers empty reassurances and photo-ops.

4. Neglect of Contractors and Economic Sabotage

It is both shocking and unacceptable that Federal Government contractors who executed infrastructure and service-based projects for national development have not been paid for over nine months. In June 2025, more than 5,000 local contractors took to the streets in Abuja to protest non-payment. Many of them are now bankrupt. Some have tragically lost their lives due to stress and untreated medical conditions resulting from financial ruin.

Let it be known that these contractors are the backbone of infrastructure and service delivery in Nigeria. When they are denied payment, schools, hospitals, roads, and water systems remain unfinished. Workers are laid off. More Nigerians fall into poverty. The economy suffers — all because this administration refuses to do the bare minimum: honour its obligations.

5. A Government that Refuses to Listen

President Tinubu and the APC have shown zero regard for public opinion, professional advice, or human suffering. Rather than admit failure and course-correct, they weaponize propaganda, distract with divisive rhetoric, and gaslight the nation with false promises.

Our Stand as ADC Youth Volunteers

As youth leaders of the ADC in the South-South and across the country, we reject this incompetence, this deception, and this collapse. The future of Nigeria cannot be mortgaged to leaders who are incapable of managing crises, who reward loyalty over competence, and who treat Nigerians as expendable political pawns.

We call on all well-meaning Nigerians, civil society organizations, religious leaders, and traditional rulers to rise and speak truth to power. The time for silence is over. A new Nigeria cannot emerge from a foundation of betrayal, hunger, and bloodshed.

Enough is Enough.

Signed,

Dr. Emaluji Michael Sunday

South-South Volunteer Youth Spokesman

African Democratic Congress (ADC)

Email: adcvolunteers.ng@gmail.com

Tel: +234 8065667809

-

NEWS2 days ago

NEWS2 days agoEnsure transparency, effective deployment of tax resources, NUJ, FCT Chair tells FG

-

SPORTS9 hours ago

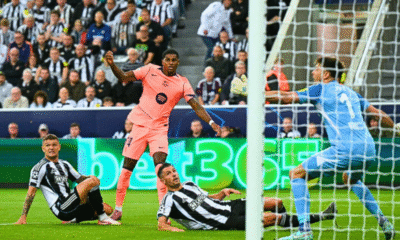

SPORTS9 hours agoBarcelona edge Newcastle 2-1 thanks to Rashford’s Second-Half magic

-

NEWS48 minutes ago

NEWS48 minutes agoNSITF mourns Afriland Towers fire VICTIMS, calls for stronger workplace safety

-

NEWS41 minutes ago

NEWS41 minutes agoSouth East NUJ hosts homecoming, awards Chris Isiguzo Lifetime Achievement Honour

-

NEWS30 minutes ago

NEWS30 minutes agoNigerian Born Int’l Journalist, Livinus Chibuike Victor, attempts to attain Interviewing Marathon of 72hours 30 Seconds