ENTREPRENEURSHIP

How $5 a Night Hostels Led to Japan’s First $1 Billion Startup

In 2012, Shintaro Yamada was 34 years old, single and frustrated with his job. So he quit a comfortable position in Tokyo and set out to see the world.

QuickTakeUnicorns

He made a point of traveling on the cheap and mixing with the locals. He stayed at $5-a-night hostels without hot water, hitching motorbike rides and hopping local buses between destinations. Over six months and 23 countries, he hiked the world’s largest salt flat in Bolivia, stayed in a nomad’s home at the edge of the Sahara desert, tracked the turtles of the Galapagos Islands and visited the tree in India where Buddha found nirvana.

“It broadened my mind, made me want to make something that could be useful anywhere in the world,” said Yamada, now 38, wearing a bright pink hoodie at the company’s headquarters in central Tokyo. “I began to think about a platform that would allow people to exchange money or things or services using their smartphones.”

Yamada struggled with ideas for education and language applications before teaming up with two other founders to establish Mercari in 2013. It reached the landmark valuation this month based on the price of equity sold in a 8.4 billion yen ($74 million) round of fundraising from investors including Mitsui & Co. and Globis Capital Partners. The company is now based in the same Roppongi Hills complex as Google Inc. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc., with hallways that show off its eclectic mix of goods including a boombox, an acoustic guitar and a stylish green bicycle.

Lone Unicorn

Though the valuation is an accomplishment for Mercari, it also highlights the dearth of major private startups in the world’s third-largest economy. There are 155 so-called unicorns in the world, according to CB Insights, with 92 in the U.S., 25 in China and seven in India. Japan has suffered from a lack of venture capital and a risk-averse culture where the best and brightest strive for stable jobs at big companies and then stay for life.

Yamada thinks the problem isn’t quite as dire as it may appear. Many tech companies in Japan go public well before they reach the $1 billion valuation mark because the country has lenient listing requirements for small, high-growth businesses. The TSE Mothers market requires just $10 million in capitalization and has no income prerequisite; companies going public on the tech-heavy Nasdaq must clear $50 million market cap or $750,000 in profit.

Still, he thinks Japan does need more entrepreneurial role models, the likes of Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg. “There are just not that many people trying,” he said. “Maybe if I do it, more people will believe that it’s possible to succeed.”

Brass Ring

Yamada is used to taking the path less traveled. He studied mathematics at Waseda University, a prestigious school where graduates typically head to the country’s top banks and blue-chip companies. Instead, he took an internship developing an auction site for Rakuten Inc., then a little-known e-commerce site. He met founder Hiroshi Mikitani and saw as he began building the company into what is now a retailing giant worth $14 billion.

Rather than stay with Rakuten though, Yamada struck out on his own after graduation. He founded a games company called Unoh Inc. (Japanese for right brain) in 2001. The company produced several hits and was acquired by Zynga Inc. in 2010.

He helped localize apps for the San Francisco-based company, an early leader in casual games like FarmVille. It lasted about 18 months. Yamada wanted to work on a project with more global scale. That led to his six-month odyssey and the founding of Mercari with fellow Waseda alumnus Tommy Tomishima and Ryo Ishizuka.

Mercari’s edge has been that it’s designed specifically for mobile phones and lets individuals easily browse through items for sale or post their own. People sell everything from clothes and electronics to baseball tickets. While its staying power remains unproven, the app has been downloaded 32 million times and generates 10 billion yen in monthly transactions, Yamada said. Mercari takes a cut of each sale.

“The market for business-to-consumer services is already quite developed, but user-to-user applications still have a lot of room to grow,” said Tomoaki Kawasaki, an analyst at Iwai Cosmo Securities Co. “Mercari is already in the lead in Japan. There are significant benefits for early movers.”

Major Battle

Yamada is now devising a strategy to boost Mercari’s presence in the U.S. — home turf for industry pioneers Amazon.com Inc. and EBay Inc. The service has been available there since September 2014 and been downloaded 7 million times, but users are tough to retain. To gain more ground, Yamada has dropped Mercari’s 10-percent transaction fee in the country and plans to use its venture money to market through social media sites including Facebook.

There are signs of progress. Mercari has climbed in rankings of shopping apps downloaded for Apple devices, breaking into the top 10 last month, according to data from App Annie. Yamada says he has no illusions about the difficulties of the upcoming battle, but winning a bigger footprint in the U.S. is essential to becoming a global company.

“If not us, then somebody else will take the U.S. market and we will eventually have to face them in Japan,” he said. “This is the case of offense being the best defense.”

BLOOMBERG

ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Franka Undie Pioneers AI Solutions In Healthcare, Garners Distinction, Special Award From Foreign Varsity

Franka Undie, a Nigerian from Yala Local Government Area of Cross River State has graduated from the RUDN University with the highest distinction in Applied Mathematics and Informatics/Data Science and Digital Transformation in her Master’s degree. Her outstanding achievements include receiving a special award for her groundbreaking scientific research aimed at revolutionizing the healthcare sector through artificial intelligence (AI).

Mrs Franca Undie Okache

Recalled that In 2019, Franka Undie captured national and international attention when she received over 20 MSc admissions from prestigious universities around the world. Opting to pursue her studies at RUDN University, she has since demonstrated unparalleled dedication and brilliance, culminating in her recent graduation with a distinction in MSc degree.

Mrs. Okache’s MSc thesis has set a new benchmark in the application of AI in healthcare. Her research focuses on developing an AI system that not only aids doctors in decision-making but also provides clear, understandable explanations for its recommendations. This innovation is designed to enhance the decision-making process in medical practice, enabling doctors to make better-informed choices based on comprehensive patient data.

Her AI system stands out for its user-friendly interface, which demystifies complex AI algorithms, making them accessible to medical professionals without extensive technical backgrounds. This breakthrough holds the potential to significantly improve patient outcomes by ensuring that medical decisions are both data-driven and comprehensible.

Franka’s exceptional work has not gone unnoticed. She was honoured with a special award by RUDN University for her scientific contributions, highlighting the impact and importance of her research in the field of AI and healthcare. This accolade is proof of her innovative spirit and the practical relevance of her work.

Beyond her academic and research accomplishments, Mrs. Franka Matthew Okache’s personal life also reflects a commitment to excellence and service. She is married to Mr. Matthew Okache ANIPR, the Chief Press Secretary to Rt. Hon. Elvert Ayambem, Speaker of the Cross River State House of Assembly. Her family and friends are immensely proud of her achievements and the positive representation she brings to Nigeria on the global stage.

BUSINESS

Towering Profile of Cross River-Born Pro African Entrepreneur, Apuye Angiating

Apuye Angiating is an experienced, multi-competent, and Pro African Entrepreneur with a proven track record of excellence in the agricultural, real estate, investment banking and healthcare sectors. He has a knack for turning ideas into creative impactful brands that address the unmet needs of the underserved and at-risk communities, focusing on developing local content/potential to compete with global brands.

Mr Apuye Angiating

He has a passion for promoting youth and women productivity, which has led to the creation of brands with an inclusive ideology evident in the composition of his team and workforce. His entrepreneurial drive to help accelerate sectorial growth and entrepreneurship is playing a pivotal role to create jobs and self-reliance in a competitive economy like ours.

Mr Apuye Angiating is a USA based Agropreneur and the MD/CEO of Uteb Agro Consult and Farms Co. Ltd, with presence in Ondo State, Ekiti State and Cross River State. A reputable and established Agroprenuer with large scale farming projects in Ondo and Ekiti States, in maize/corn cultivation, creating employment for several members of these states. From the humble beginning as a small-scale farmer in Akure, Ondo State, his journey into agriculture and farming has been one of continuous growth and innovation.

Over the years, he has expanded his operations to encompass 175 hectares of farmland with ambitious plans to reach 1000 hectares and beyond within the next five years. This expansion is not just a testament to his vision but also a reflection of his unwavering commitment to promoting agro-allied services and driving sustainable growth in Nigeria’s agricultural sector. Innovation is at the heart of everything he does, from precision agriculture techniques to the adoption of climate smart practices, he is constantly exploring new ways to enhance productivity.

In a bid to promote indigenous excellence, Mr. Angiating has established the Superfine Vegetable Oil Factory in Bebuagbong Village, Ipong, Obudu LGA of Cross River State. The Superfine Vegetable Oil Factory is a testament to his commitment to local empowerment and sustainable development. As the first indigenous vegetable oil factory in Cross River State, he takes immense pride in pioneering an era of agricultural excellence. With state-of-the-art oil processing machines and a cutting-edge oil refinery, the superfine vegetable oil factory epitomizes the fusion of tradition and technology, delivering unparallel quality with every oil drop. Superfine vegetable oil is produced, refined and packaged to perfection in nutritional value in the 21st century.

The Uteb Agro Mentorship Hub pioneered and powered by Mr Apuye Angiating is a catalyst for entrepreneurial growth and development providing support, resources, and mentorship to budding entrepreneurs and established businesses alike. Through this mentorship program, he provides agricultural inputs and financial support to women and youths who aspires to venture into agriculture. Mr. Angiating is also planning a scholarship scheme to support Northern Cross River State students who are studying agriculture in tertiary institutions.

Currently Mr. Angiating is looking homeward with a proposed plan to establish cassava and maize projects in Cross River State. The discussion is on-going with the Commissioner for Agriculture, Cross River State and other community stakeholders.

As an Innovative entrepreneur, over the years he has created and established new business models to generate profit, accomplish company goals, and assist his community. With applied creativity, he has identified opportunities, developed innovative business models to meet consumer needs, improved market competitiveness, and transform ideas into business success. These are vital in driving economic growth, creating jobs, and addressing modern societal needs to push the boundaries of progress.

Considering his Entrepreneurial pedigree, Mr Apuye Angiating has been nominated as the Innovative Entrepreneur Man of the Year 2024 by Yala Achievers Award which is slated for July 28th at Transcorp Calabar, Calabar . This is to celebrate his remarkable accomplishments of who has shown immense and outstanding entrepreneurial innovation, leadership, creativity, and dedication towards providing gainful employment for Cross Riverians and Nigerians at large. The growing importance of Apuye’s works highlights his crucial role in encouraging innovation, inspiring future entrepreneurs, and driving economic growth.

Apuye Angiating holds a Master’s degree in Social Work from the prestigious Howard University, Washington DC, USA. He is married to Victoria Utebye Angiating and the marriage is blessed with three lovely kids

ENTREPRENEURSHIP

National Career Fair Moves To Provide 6000 Jobs Nationwide

Nigeria’s biggest annual symposium on career information, business development, employment and economic opportunities for students, young professionals and SMEs in Nigeria, National Career Fair, NCF, has moved to provide 6000 fresh jobs for unemployed graduates nationwide.

The annual event which is back for its 6th edition is designed to reduce the growing unemployment rate in Nigeria and respond to the growing needs of the society- student undergraduates, graduates through an all-encompassing career information program; and has this year introduced a Nationwide campaign tagged “#EmployAnIntern” in a bid to create instant jobs for Youths and students.

According to the convener of the NCF, Oluwaseun Shogbamu, “The #EmployAnIntern campaign is designed to engage a growing Nigerian workforce positively. The campaign encourages Organizations, to employ interns all around the country on the NCF platform that have been trained in work etiquette and professionalism either on the short or long term basis. The campaign is directed at both established companies and entrepreneurs, thus opening the minds of students, job seekers and youths to a whole new world of job descriptions they never thought existed.”

He added that the nationwide tour of the annual free symposium which will begin in Lagos at the Main Auditorium of the prestigious University of Lagos on the 7th of December, 2017 will be held across the six geo-political zones in the country and will also feature sixty (60) speakers and professionals while partnering with top HR personnel, Vocational training institutes, as well as Capacity Building-Oriented oraganisations.

The organisers of the National Career Fair however urged youth to take advantage of its platform to enhance personal branding by either volunteering for the event in various states or applying for various job and internship opportunities to be provided during the course of the nationwide tour.

-

NEWS2 days ago

NEWS2 days agoEnsure transparency, effective deployment of tax resources, NUJ, FCT Chair tells FG

-

SPORTS9 hours ago

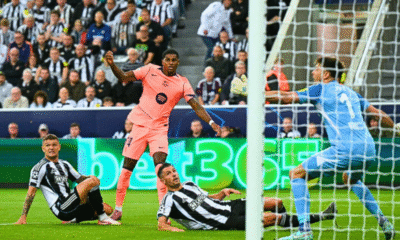

SPORTS9 hours agoBarcelona edge Newcastle 2-1 thanks to Rashford’s Second-Half magic

-

NEWS28 minutes ago

NEWS28 minutes agoNSITF mourns Afriland Towers fire VICTIMS, calls for stronger workplace safety

-

NEWS21 minutes ago

NEWS21 minutes agoSouth East NUJ hosts homecoming, awards Chris Isiguzo Lifetime Achievement Honour

-

NEWS10 minutes ago

NEWS10 minutes agoNigerian Born Int’l Journalist, Livinus Chibuike Victor, attempts to attain Interviewing Marathon of 72hours 30 Seconds